1. Introduction

This article analyzes the relationship between motivation and organizational support for individuals who are part of the so-called Generation Y. Also known as “the children of technology” (Tapscott, 2008), individuals who are part of this generation tend to be motivated by challenges. Work, in their perspective, is much more than a source of income, since their motivation lies in the quest for knowledge, learning and satisfaction (Lombardía, Stein, & Pin, 2008).

There is no consensus among authors about the time span that defines the beginning and end of this generation, and it may vary between those born in 1981 and 2001 (Howe & Strauss, 1992), between 1978 and 2000 (Tulgan, 2009) and between 1979 and 2000 (Cerbasi & Barbosa, 2009). On the other hand, from a broad perspective, studies depict this generation as one connected to brand-new technologies of information and communication, and driven by challenges of innovation and entrepreneurship. In order to carry out this study, individuals born between 1981 and 2001 were considered as part of Generation Y. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that any generational definition must take into consideration the specific traits and historical milestones contributing to the formation of the generational group’s viewpoint (Rocha-de-Oliveira, Piccinini, & Bitencourt, 2012). The date of birth is not the only element that groups together people of the same generation; historical processes and the way these events are experienced by different age groups are also important factors (Tomizaki, 2010). There fore, a study centered on Brazil’s Generation Y may encounter different characteristics in comparison to a study focused on young people who are part of the American or European Generation Y, as they belong to developed countries, with historically different experiences from those experienced by young Latin Americans.

In the Latin American context, studies have pointed out that Generation Y does not consider job security as pivotal, being focused instead on learning values of their generation (Zavala-Villalón & Frías Castro, 2018). Individuals who are part of this generation also tend to prioritize the balance between personal and professional life rather than job security and higher wages (Silva, Dutra, Veloso, Fischer, & Trevisan, 2015; Twenge & Campbell, 2012), as they attempt to find a flexible and information-sharing environment (García, Gonzales- Miranda, Gallo, & Roman-Calderon, 2019; Veloso, Dutra, & Nakata, 2016; Reis & Braga, 2016).

Generation Y’s behavior has been the source of major challenges to companies, such as understanding the motivational elements in Generation Y’s work environment (Allen, 2005). Falaster, Ferreira and Reis (2015) state that Generation Y has high regard of sustainable companies whose routines are flexible and dynamic, enabling positive personal interactions between colleagues and leaders in a friendly environment, and with less authoritarian management.

The relationship between leaders and subordinates of this generation deserves to be thoroughly assessed, since the latter expect a high level of feedback, centered on personal and professional success, personal attention, empowerment and the need for freedom, flexibility and meaning (Hannus, 2016; Allen, 2005). This reality makes motivation a challenge for companies and requires new approaches to leadership and organizational support, in order to maximize the commitment and the establishment of long-lasting bonds as well as the engagement of Generation Y (Perrone, Engelman, Schaurich Santos, & Rodrigues Sobrosa, 2013).

Several studies have also emphasized the importance of organizational support (OS) and the influence of support provided by the manager on the motivation of Generation Y employees. Du Plessis (2013) stresses that the positive relationship between the OS and manager support (MS) has a direct influence on workers’ perception and will result in lower turnover for the institution. Pinho (2014) argues that Generation Y needs the presence of the manager and both the OS and the SM are independent, but work quite well together and are decisive for employee satisfaction. Madero-Gómez and Olivas-Luján (2016) present a positive relationship between organizational support and job satisfaction among young people starting their careers.

Following on from the notion that the leader/follower relationship is an important factor in the relationship between motivation and the OS (as perceived by Generation Y), the objective of this study is to detail the influence of OS and leader relations on Generation Y’s work motivation. The following objectives were determined to accomplish this goal: a) to describe the influence of OS on the intrinsic motivation of individuals who are part of Generation Y and b) to show how the support provided by managers moderates the relationship between organizational support and Generation Y employees’ motivation.

To attain this objective, Self Determination Theory (SDT) motivation will be defined (Ryan & Deci, 2000b; Gagné & Deci, 2005). Secondly, a review of the literature on the subject of Organizational Support (OS) will be presented (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, 1986).

The relationship between members of Generation Y and their managers will be analyzed based on the Leader Member Exchange (LMX), focussing on how the quality of the manager/ subordinate relationship influences Generation Y employees. This influence not only manifests itself in the perception of support, but in its relationship towards work motivation. Leaders must motivate, provide support, develop talent, and communicate, mainly through values and examples in their management (da Silva & Struckel, 2013).

The method used in this quantitative survey research study included a cross-sectional cohort and the use of a closed-question questionnaire, with options on a 1-5 Likert scale. 326 individuals belonging to Generation Y, from different Brazilian regions, participated in this study. The data analysis followed the criteria of reliability and adequacy of the model, assessed by Cronbach’s Alpha and the Confirmatory Factor Analysis, and the hypotheses were tested with the use of linear regression and moderation.

The article is organized into four sections. The first presents the research's theoretical framework. In the second section, the methodological aspects of the research will be presented. In the third section will be made the analysis and discussion of the results found. The study concludes with final considerations on the results, limitations and suggestions of future studies.

2. Theoretical framework

The section presents the research's theoretical framework: Self-Determination Theory, The Leader-Member exchange (LMX) and the organizational support. This presentation aims to relate these different perspectives and support the hypotheses of the study.

2.1. Self-determination theory

Motivation is a complex concept, studied in different fields of knowledge. Motivation can be depicted as a driving force with hidden sources within each human being (Bergamini, 2000), or also as a reason, purpose or stimulus found in each human being that motivates them to search for something specific.

In the organizational field, the very first studies about human motivation emerged given the need to find a pattern for all employees and institutions. It was believed that monthly remuneration (wages) was the main source of motivation and encouragement for people to generate better productivity and results (Miranda, 2009).

Lately, SDT has been widely used to study motivation within a multidimensional perspective. SDT suggests a model that observes peoples’ psychological needs, clarifies the actions and skills of each individual, as well as the principles of their intrinsic (from within the individual) and extrinsic (externally regulated) motivation. SDT considers social context as an agent of influence of human behavior, both in development and in demotivation (Engelmann, 2010). Therefore, SDT provides a better understanding of a person’s motivation and trust in their own abilities and skills. According to the authors, all human beings have the following basic psychological needs: the need for autonomy, the need for competence and the need to be part of something; and the satisfaction of needs is essential for personal development, growth and personal inclusion in the work environment (Ryan & Deci, 2000b).

Numerous studies have confirmed SDT as a predictor of engagement (Gillet, Huart, Colombat, & Fouquereau, 2013), from the perspective of manager autonomy (Gillet, Gagné, Sauvagère, & Fouquereau, 2013), commitment (Mahmoud, 2008) and reactions to new technologies (Mitchell, Gagné, Beaudry, & Dyer, 2012). Based on SDT, research by Weinstein and Hodgins (2009) shows that those participants with greater autonomy to carry out activities experienced better satisfaction, persistence, energy and well-being, contributing to the assumption that autonomy simplifies effective regulation and promotes positive results.

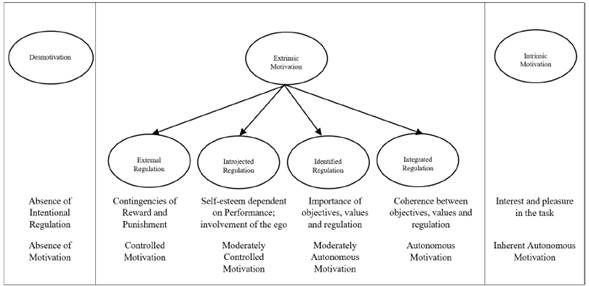

SDT continues to be a conceptual reference for evaluating different motivations. Figure 1 demonstrates the continuum between a lack of motivation and intrinsic motivation.

Figure 1 shows that motivation is a reason that withstands the actions of every single human being. Self-determination theory has two fundamental components: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Chen & Jang, 2010). Intrinsic motivation is seen as a mediator in a person’s acquisition of skills (Lopes, Pinheiro, da Silva, & de Abreu, 2015). According to Ryan and Deci (2000a) intrinsic motivation is related to humans’ natural ability to pursue challenges and novelties, it also symbolizes the capacity to conduct a specific action voluntarily, for the simple pleasure of accomplishing it. These constitute fundamen-tal characteristics for cognitive development and social inclusion.

Figure 1 Continuum of self-determination, types of motivation - the locus of causality and regulatory processes.

Extrinsic motivation is related to the execution of specific activities in order to achieve external results. For Guimarães (2004), extrinsic motivation is actually a motivation to work for external actions, to achieve social/professional acknowledgement, to be given bonuses, to be rewarded, even the need to accomplish demands in order to demonstrate competence.

The relationship between SDT and work motivation lies in the support provided by the leader (Deci, Connell, & Ryan, 1989), since the autonomy and trust given to the employee by their manager positively influences motivation, whereas more controlled support has a negative influence (Gagné & Deci, 2005). The positive relationship between the employee and the manager is the factor that determines organizational perception, a relationship of trust and autonomy increases motivation and also employee satisfaction (Madero-Gómez & Olivas-Luján, 2016; Baard, Deci & Ryan, 2004; Deci, Ryan, Gagné, Leone, Usunov, & Kornazheva, 2001; Gagne, Koestner, & Zuckerman, 2000; Ilardi, Leone, Kasser, & Ryan, 1993; Kasser, Davey, & Ryan, 1992).

Based on SDT literature and studies available on Generation Y’s motivation, this study focuses on intrinsic motivation, associated with pleasure and satisfaction in work, particularly considering the characteristics of autonomy, flexibility, space for creativity and the need to sustain positive relationships. The characteristics of the “Intrinsic Motivation” factor will be outlined in the methodology and in the analysis of the results.

2.2. Support provided by the organization and manager

The subject of OS is relevant, given its contribution to a better quality of life in the institution, as well as its influence on physical and mental health, the sense of belonging, decreased turnover and increased productivity. OS is perceived through a psychological aspect, in other words, the perspectives interpreted by the employee in relation to their treatment within the institution, which may eventually influence the relationship between the employee and the institution, as well as motivation and efforts to accomplish work tasks (Berthelsen, Hjalmers, & Soderfeldt, 2008).

OS is referred to as assistance provided by the institution, which influences the employee’s safety. This support from the institution promotes the well-being and satisfaction of employees, increasing quality of life at work and the perception of OS (Chaves Correia-Lima, Loiola, Pereira, & Guedes Gondim, 2017).

The perception of OS is also related to the employee’s health and can have a negative impact on the work environment. An intense emotional load, pressure to achieve goals, negotiation, confrontations, changes, all constitute daily phenomena that can generate psychological issues such as stress, depression, and emotional exhaustion directly affecting both the employee and the institution (Tamayo & Tróccoli, 2002; Covacs, 2006).

Harter, Schmidt and Keyes (2003) confirm that well-being at work still depends on the quality of support provided to employees, by acquiring the conditions necessary to provide activities that will show the institution’s expectations. Basic needs at work range from the clarification of what is expected from the employee, to the support required to accomplish the activities, raw materials and resources. Other studies show that this support corresponds, at least partially, to the credibility that the employee may have within the institution (Covacs, 2006).

According to the literature on the subject, OS is a predictor of employee autonomy (Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhoades, 2002; Gagné, 2003; Gillet et al., 2013), well-being and motivation (Estivalete, de Andrade, Faller, Stefanan, & Souza, 2016), and organizational trust (Stinglhamber, Cremer, & Mercken, 2006). OS is an important factor for well-being in the institution, hence the leader’s importance as a mediator to expand organizational perceptions (Paschoal, Torres, & Barreiros Porto, 2010).

Managers must act as institutional agents, whose role is to moderate the relationship between the institution and the employee, in which the primary responsibility is to guide, instruct and assess the performance of the employee’s actions (Hochwarter, Witt, Treadway, & Ferris, 2006). This support may also manifest itself negatively, which will have greater impact in the context of high-level leadership and contributes to voluntary employee turnover (Eisenberger et al., 2002; Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003).

Institutional commitment to employees influences cooperation between employees and OS, a relationship that solidifies engagement and motivation for the institution (Siqueira & Padovam, 2008). When there is perceived support at work, the development, performance, and engagement of the employee will take place naturally, improving job satisfaction and well-being, as the employee identifies themselves with the institution.

2.3. Leader-member exchange (LMX)

Generation Y employees’ need for constant feedback on their performance is also emphasised in research by Lipkin and Perrymore (2010), revealing managers’ difficulty in elaborating constructive criticism to motivate such individuals. Furthermore, individuals of this generation seek transparent relationships with their immediate hierarchical superiors and are unafraid of turnover (Lombardia, Stein, & Pin, 2008). This condition presents yet another challenge for managers who need to activate the creativity and involvement of their subordinates, making them motivated and engaged in a way that allows them to feel part of the institution, since good wages, aggressive demand and layoffs are ineffective, and insufficient to keep them in tune with the institution (Lancaster & Stillman, 2011).

The theory of exchange between leader and employee (known as Leader-member exchange or LMX) suggests that several elements may eventually influence employees’ behavior, motivation and actions, including the manager’s way of leading, and resulting in the type of relationship established between the manager and the employee (de Oliveira & da Costa Rocha, 2017). Furthermore, for workers of Generation Y, there is a positive relationship between engagement and job satisfaction, as well as a greater positive impact on satisfaction when they participate in decisions about general aspects of the company (García et al., 2019).

LMX theory states that leaders may develop different relationships with employees, the relationship with each employee can be distinct, influenced by an exchange of experiences, trust, similarities, or a created identity (Brant, 2016). There is a perception among employees on the qualitative difference of the leader’s relationship between one group and another, a matter often related to the allocation of more time or resources (Oliveira & da Costa Rocha, 2017).

According to Harris, Li and Kirkman (2014), there are situations in which the leader has a higher-quality relationship meaning that differentiation between groups is lower, and the work team is reciprocal and engaged. Therefore, when there is a perception of differentiation, the work team represses itself and ends up neutralizing desirable relationships between the leader and the institution. On the other hand, organizational support can improve employee motivation and thus strengthen the quality of the manager-employee relationship (Santos, 2012).

Generally speaking, one can attest that a quality relationship between leader and employee (LMX) increases the perception of OS, improves organizational performance (Selvarajan, Singh, & Solansky, 2018) and develops trust among employees. It is a relationship that may determine satisfaction, empowerment, engagement and motivation of employees in relation to the institution (Malik, Wan, Ahmad, Naseem, & ur Rehman, 2015).

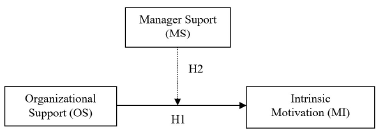

Based on these theoretical arguments, this study will test the following hypotheses:

H1: organizational support has a positive and meaningful influence on the intrinsic motivation of individuals who are part of Generation Y.

H2: manager support moderates the relationship between organizational support and the intrinsic motivation of Generation Y employees.

Therefore, we suggest the following model of analysis. Figure 2 illustrates the theoretical model of the study.

3. Methodology

The objective of this study is to analyze the influence of organizational support on Generation Y employees’ work motivation. In order to do this, a quantitative research survey was conducted, with a cross-sectional cohort (Malhotra, 2012). Survey research determines the occurrence and classification of the characteristics and opinions of populations and people, attributing to work the characteristics of small, but presumably representative samples of such populations (Kerlinger, 1979).

The study is also descriptive, which allows us to draw conclusions about the data collected from planned and structured research instruments (Malhotra, 2012). The text encompasses observations involving a descriptive part of what takes place and a reflexive part, which contains personal observations of the researchers on the results of the data collection (Godoy, 1995).

The method of data collection used was a cross-sectional questionnaire and a 1-5 Likert scale. The data were collected using an online questionnaire between May and June 2018. The questionnaire was hosted on the Qualtrics® platform. The study sample consisted of 326 respondents, aged between 17 and 37 years old.

Regarding data processing, the questionnaires were entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, after which the information was submitted to a database developed through statistical analysis software, the IBM SPSS Statistics v.2.1 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). Descriptive statistics, a regression and moderation analysis were used. For the moderation analysis, scales were standardized using the Z-score technique to reduce the effects of multi-collinearity (Field, 2013).

Cronbach’s Alpha (α) was used to assess the internal consistency of the scales. For the motivation construct, the alpha of the Intrinsic Motivation factor, composed of nine variables, was 0.823, while the alpha of Extrinsic Motivation was 0.755. As for the organizational support construct, the alpha for the Company Support factor, with six variables, was 0.755, while the Manager Support factor, with five factors included, was 0.901. It is observed that all measures ranked above the minimum required index to validate the consistency of the data collection instrument (α ≤ 0.700).

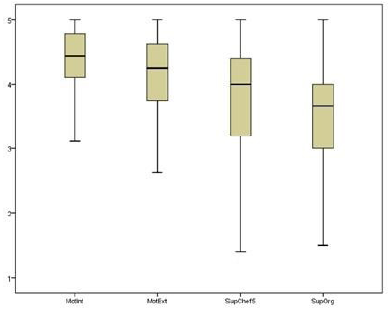

Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to measure the degree of association between the variables, using table-based descriptive statistical analyses with graphical representation (Box-plot). The analyses were conducted by the IBM SPSS Statistics package (v. 21, Chicago IL). An error probability of 0.05 was taken into consideration in all inferential analyses.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) is a multivariate analysis technique used to verify whether the hypothetical model adjusts the data, in other words, whether the four factors of the model (Motivation - intrinsic and extrinsic, Organizational Support and Managerial Support) were adjusted based on the data collected. The indicators used in this study were questions organized in a structured questionnaire, in which the respondents indicated their choices on a Likert-type scale. CFA was used to group these indicators, which are manifest variables, centered on factors, which are latent variables that were not directly observed (Hair et al., 2009).

CFA was used in this study since it attempts to confirm the factors present in the scales used and validated in previous studies. The confirmation of factors was conducted using the Varimax with Kaiser Normalization rotation method. The CFA is an important step for verification of the analysis’ structural model. The construction of the model followed the precepts of Structural Equation Models (SEM), used to analyze the relationships between the multiple observed variables and the latent variables or factors of a construct (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2016).

The indices observed in this study were the Chi-square (x²) and degrees of freedom (df), along with the Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI), Trucker Level Index (TLI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). X² displays the magnitude of the discrepancy between the observed and modeled covariance matrix, testing the probability of adjusting the data to the theoretical model. The x²/df relationship was observed based on the confidence interval between 1 and 3 (Kline, 2005). The CFI measures the relative improvement of the fit of the proposed model to a standard model. Unlike the CFI, the TLI does not normalize the data, and it may express values outside the range of 0 and 1. Nonetheless, the TLI is interpreted similarly to the CFI, regarding values close to 1 as a well-adjusted model. For the CFI and the TLI, values above 0.90 point to an appropriate model. The RMSEA is a measure of discrepancy based on chi-square’s non-centralized distribution, expressing the model’s poor specification degree. Values below 0.05 are ideal, but scores up to 0.08 are acceptable (Kline, 2005).

After analyzing the fit of the model, linear regression was used to analyze the predictive ability of the independent variable Organizational Support (OS) on the dependent variable Intrinsic Motivation (IM). Linear regression allows the interpretation of the model’s explanatory capacity, measured with r², of the statistical significance of the relationship between the independent and the dependent variable (p) and the coefficient of variation of this same relationship, measured by the standardized beta (β). It is important to take into account that the higher the r2, the greater the model’s explanatory capacity, measured as a percentage, whereas “p” measures the confidence interval (95%, < 0.005) and β measures the direction (positive or negative) and strength of the relationship. The closer to zero the beta is, the lower the influence intensity.

Based on this analysis, a moderation analysis was suggested, in which manager support (MS) was established as a moderating variable of the relationship between OS and IM. The moderation effect corresponds to a variable that influences the direction or intensity of the relationship between a predictive variable (independent) and a dependent variable (Baron & Kenny, 1986). This moderation takes place in certain validity conditions, especially due to intensity, strengthening of the relationship between X and Y, or even changes in the direction of this relationship (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The moderation analysis followed the proposition by Aiken and West (1991), allowing the creation of a graph of combinatorial estimates between high and low values of the independent variable OS and the moderating variable MS on the dependent variable IM. The SPSS macro process was used for the moderation analysis and regression coefficients were measured using the Johnson-Neyman technique (Hayes, 2013). In addition to verifying the interaction’s direct and indirect effect and generating information from the analysis model, the macro allows the creation of graphs to identify regions of significance, displaying the effect of the moderation based on the ranges of values found.

The respondents answered a 31-question survey with two scales: the Scale of Organizational Support (OS) from Eisenberg et al. (1986) and the “Motivation at Work Scale” developed by Gagné et al. (2008). This study used the transla-ted and adapted version by Chambel, Castanheira, Oliveira- Cruz and Lopes (2015). At the end, participants also filled out sociological information. In accordance with established research ethics, the study followed the recommendations of the Resolutions of the National Health Council (CNS) no. 466 of December 12, 2012 and CNS 510/16 of April 7, 2016 and of the Handbook of Good Practices of the National Association of Postgraduate Studies and Research in Administration (ANPAD).

4. Analysis of the results

After checking the data using a normality, multicollinearity, missing-values and outliers test, a reliability test was applied to the scales. Cronbach’s Alpha test was used, which requires values above 70 to indicate an internal consistency of the scale (Hair et al., 2009). The motivation scale had an alpha of 0.869 and the OS alpha was 0.941. Taking into account the OS factors that comprise the theoretical model of this study, the Organizational Support alpha was 0.901, whereas Manager Support had 0.905. The tests conducted confirmed that the scales have good internal consistency.

Regarding the social characteristics of respondents, the sample consisted of 54.6% females and 45.4% males, and 67.8% of the respondents are attending or have already completed a degree or a postgraduate degree, while 84.4% of respondents said they have chosen their profession. The criteria for inclusion in the sample were: a) having, at the date of participation, an age between 17 and 37 years old and b) being regularly employed.

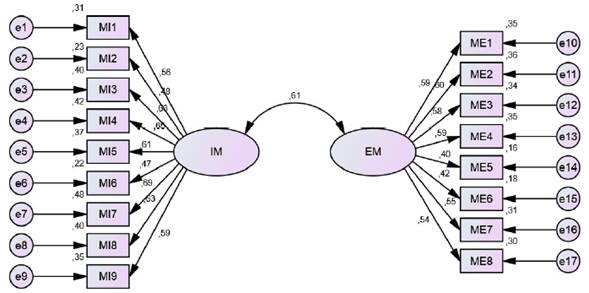

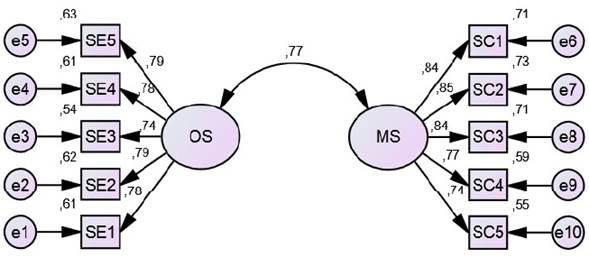

CFA was the technique used to define the convergent and discriminatory validity of the measures used. The result confirmed the division of the motivational scale into two factors (Figure 3), named Intrinsic Motivation (IM, with nine variables) and Extrinsic Motivation (EM, with eight variables). SEM was used to measure the fit of the model, presenting indices r²/df = 3.06, RMSA = 0.081, TLI = 0.901 and CFI = 0.928. These indices are within the acceptable range to consider fitting the model as appropriate.

Figure 3 Diagram of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Motivation Constructs.

SEM was also used to analyze the fit of the organization and boss support model. The analysis of the interactions presented very low values between the variable six and the factor Organization Support, which led to the exclusion of this item, leaving the model with five variables associated with the factor (Figure 4). The model presented the following results: x²/df = 4.2, CFI = 0.937, TLI = 0.917, RMSE = 0.085. It can be seen that the Chi-square (x²) division by the degree of freedom (df) generated a value of 4.2, above the level suggested for a good statistical model (≤ 3), but within the limit of 5, which allows us to accept the model, as supported by Tanaka (1993). The RMSEA (= 0.085) also showed indices outside the suggested limit (≤ 0.08), something that can be explained by the size of the sample, since this measure does not behave satisfactorily in “small” samples (Iacobucci, 2010).

Figure 4 Diagram of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Organizational Support Constructs.

For the descriptive analysis of the motivation variable, assessed through the level of importance that respondents give to work environments, the average of the scales and the stand-ard deviation (σ) were taken into consideration. Individuals from Generation Y believe that the most important thing is to achieve personal fulfillment (4.58, σ=0.669), such as through the tasks performed (4.52, σ=0.862) and the pleasure taken from work (4.50, σ=0.668). The results show that Generation Y is motivated not only by the wages or benefits offered by the institution, but also by self-development and personal satisfaction.

The less significant results for Generation Y are the material benefits they are given (3.97, σ=0.892) and “being employed while I can’t find a better job” (3.73, σ=1.120). This concurs with the theoretical framework, which states that this generation seeks challenges and that financial compensation is not enough to keep them engaged.

Likewise, a descriptive analysis of the OS variable was performed, analyzing what Generation Y respondents take into account in the workplace regarding the institution and management. The answers that had the highest level of significance according to the average of the scales were if the employee has a good working relationship with the manager (4.02, σ=0.967), if the manager trusts the employee to stand for the latter’s decisions even when absent (3.74, σ=1.027) and if the manager recognizes their potential (3.70, σ=1.124). The answers show that Generation Y needs to have a good relationship with the leader, the leader has to trust them, and they need to be praised for their performance.

The variables with the lowest averages were “The company cares about the employee’s well-being” (3.45, σ=1.094), “the company takes into account the goals and personal values of the employees” (3.39, σ= 1.095) and “the company takes into account the interests of the employee when making a decision that directly affects them” (3.18, σ=1.154).

The results show that the highest averages are related with the “manager support” factor, reinforcing employees’ appreciation of this item. As referred to in theory, leader must motivate, provide support, develop talent, and communicate, particularly through values and examples in their management, which this generation deems relevant (da Silva & Struckel, 2013).

Figure 5 compares the averages of the factors associated with motivation (intrinsic and extrinsic) and the support (organizational and leadership).

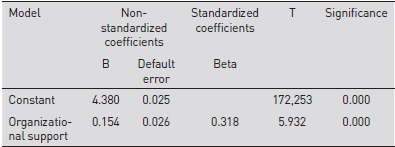

After the frequency and descriptive analysis, the first hypothesis tested was the influence of OS on the intrinsic motivation of Generation Y (H1). The hypothesis was confirmed with a highly significant correlation (p = 0.000; β = 0.318) between the two constructs and with an explanatory capacity of the model (r²) of 0.101. The results according to Table 1 can confirm that OS influences Generation Y.

Table 1 Influence of organizational support on intrinsic motivation

Dependent variable: intrinsic motivation

Source: own elaboration .

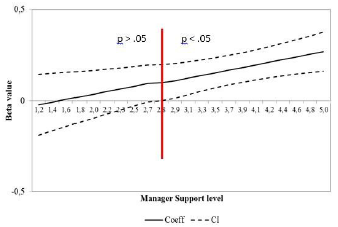

The second hypothesis was then tested, concerning the moderating effect of the relationship with the leader on the association between OS and the intrinsic motivation Generation Y employees.

The moderation analysis provides the values of significance of the indirect effect to be used in the region of significance technique, provided by the Macro Process. Figure 6 shows that, based on 2.765, moderation becomes significant (p = 0.05), in other words, as manager support increases, the effect becomes positive. The dashed lines represent a 95% confidence interval (upper and lower bootstrapping of 95%), since there can be no “zero” effect or change of direction in this interval (Hayes, 2013)

Figure 6 Moderating effect of the leader’s influence on Generation Y’s intrinsic motivation.

Figure 6 allows the observation of the level of significance, based on non-standard betas and on upper and lower confidence intervals. The analysis shows that moderation is negative until -1.156, after which it begins to exert a positive and significant effect (p = 0.05), demonstrating that there is a moderating effect of the leader in the interaction between organizational support and the intrinsic motivation of Generation Y.

These results demonstrate the importance of general OS in the intrinsic motivation of the individuals belonging to Generation Y, indicating that leaders are institutional moderating agents, ideally acting as a bridge between institution and employee. Such leaders guide, instruct and evaluate the performance of their employees, actions that served as indicative or as OS. This conclusion is in line with SDT theoretical proposition when affirming that OS is manifested in the employee's perception of your importance to the company, as well as in the satisfaction of their rela-tionship with the manager, positively influencing their commitment (Eisenberger et al., 1986).

Therefore, for Generation Y, intrinsic motivation is directly associated with the perception of OS, but is significantly moderated by manager support. Thus, it is possible to establish a relationship between quality of leadership and motivation, a result similar to that encountered by Nunes and Gaspar (2017), who have shown that the relationship between manager and employee has an influence on the motivation and engagement of the latter towards the institution (Nunes & Gaspar, 2017) and positive personal interactions with leaders, provided that management is not authoritarian (Falaster et al., 2015). Likewise, the study reinforces the conclusions of Meleiro and Siqueira (2005), Sant’Anna, Paschoal and Gosendo (2012), Seidl and Tróccoli (2006) that the relationship with management is a variable that substantially influences motivation, nurturing the well-being of employees.

Briefly put, the results follow trends identified in Latin American studies on the expectations and characteristics of the work sought by Generation Y (Zavala-Villalón & Frías Castro, 2018; Silva et al., 2015; Twenge & Campbell, 2012; García et al., 2019; Veloso et al., 2016; Reis & Braga, 2016), the influence of organizational support (Madero-Gómez & Olivas-Luján, 2016) and the influence of leader relationships on Generation Y employee motivation (Hannus, 2016; Allen, 2005). The additional contribution of this study was to show how manager support moderates this relationship between organizational support and intrinsic motivation. Therefore, the results of this study suggest the need of a more complex model to understand the behavior of Generation Y in work environments.

The quality of the relationship with the manager is a decisive element of Generation Y’s work motivation, and it may even change their perception of OS, also affecting their work motivation.

5. Conclusions

The present study describes the influence of OS on the motivation of Generation Y employees, in order to understand why this generation can have difficulties establishing long-lasting bonds in the companies where they work. The confirmation of (H1) served as the foundation for the moderation analysis (H2), indicating the moderating effect of manager support on the relationship between the perceived support of the organization and motivation to work.

The study indicates that, according to Generation Y, the work environment is decisive for their perceptions of OS. Future prospects, pleasure obtained from work, self-development, enjoying what one does and the need to feel competent and part of the work environment is crucial to the motivation of Generation Y.

Social exchanges between manager and employee are also a factor that influences OS perception. This means that the manager is a key actor, since they moderate the relationship between the perception of OS and the motivation of the Y in the organization.

Among the main theoretical implications, the present study provides an integrative model between three theoretical perspectives, which are important for understanding human behavior in organizations: SDT, OS and LMX. The findings suggest that the manager’s acknowledgement of potential, trust and consideration for what employees do are essential factors to stimulate motivation of Generation Y in the organization’s environment, and may create more lasting ties.

From a managerial standpoint, the results emphasize the importance of training managers, especially the line managers, to improve their relationship with individuals of Generation Y. Providing constant feedback and stimulating creativity and innovation, while also providing support for personal needs, are positive strategies for motivation and perception of organizational support.

To address some of the limitations identified in the course of this study, future scholars may consider conducting research on the effectiveness of this theoretical model when applied to a specific analysis of the bonds between Generation Y workers and their organizations, including the intensity and the expected duration of the relationship between individuals of Generation Y and the organizations in which they work.