1. Introduction

In the 1970s, the first studies on this topic began to take shape. Belk (1976) presented and tested a gift selection model based on cognitive consistency theories. Among the various functions of gift-giving, those of communication, social exchange, economic exchange and socialization stand out. However, the main function of the gift is to enable symbolic communication between the gift giver and the gift recipient (Belk, 1976).

The act of buying is part of a more complex process, ranging from selecting the gift to building the relationship (Davies, Whelan, Foley & Walsh, 2010). Gift-giving is initiated by an event (or occasion), involving a considerable investment in terms of financial resources, time and effort, with some type of expectation regarding consequent results in the relationship.

Among the studies on gift-giving, several motivations are identified that lead to the purchase of gifts. According to Beatty, Kahle, Homer and Misra (1985), people give gifts for three main reasons: to give pleasure, to obtain pleasure or out of obligation. Belk and Coon (1993), in turn, claim that people give gifts because they want to express feelings.

Obligation and reciprocity are characteristics typically observed in studies on the act of giving. The obligation can present itself as the main motivation for the purchase of a gift, as occurs, for example, on Valentine's Day (Rugimbana, Donahay, Neal & Polonsky, 2003). The obligation to give may also be accompanied by the obligation to give back (Belk & Coon, 1993).

On the other hand, some contextual factors influence the gift giving act, two of which are frequently studied in the extant literature, namely culture and gender (Davies et al., 2010). The cultural context in which the gift is given includes not only the relationship between the parties, but also the wider social context. The gender (mainly of the person who gives the gift), already considered an important factor in consumer behavior studies, becomes even more significant in the gift-giving act (Davies et al., 2010).

Once people present distinct perceptions and actions regarding gift-giving, it becomes important to understand the factors influencing such differences. Some studies point out that personal values reflect a set of motivational factors that significantly influence the individuals' attitudes and behaviors (Beatty et al., 1985; Borg, Bardi & Schwartz, 2015).

In this sense, Schwartz’s (1992) Theory of Personal Values presents itself as a possible theoretical lens for understanding consumer behavior with regards to the gift-giving act. Through the “values hierarchy” approach, it is possible to map the value system of a group of individuals by analyzing a psychographic or cultural characteristic that influences their way of acting and the direction of their behaviors (Borg et al., 2015). This kind of approach presupposes coherence between the declaration of values and the consumers’ behavior, making it the most appropriate choice for the purposes of this study.

This paper aims to fill a gap in the literature on Gift-giving Theory by incorporating Personal Values Theory in understanding the attitudes and behaviors of consumers in the act of gift-giving. Thus, the main objective of this study is to propose and validate a model to determine if personal values influence the attitudes and behaviors observed during the act of giving, while also considering the role of gender in these relationships. To this end, a survey was conducted with an online panel of Brazilian consumers. The stratified sample consisted of 1,085 individuals of both sexes, covering all age groups (over 18 years), marital statuses, socioeconomic classes and states in Brazil. The data was analyzed using factor analysis and structural equation modeling.

Broadening comprehension of factors that influence perceptions and consumers’ behavior in regards to gift-giving is relevant not only in academic terms, but in managerial terms also (Ferrandi, Louis, Merunka & Valette-Florence, 2015). On the other hand, for Davies et al. (2010), there have been few attempts to apply consumer behavior models in the context of gift-giving, with a limited number of rare cases where these models were empirically tested. Consequently, linking studies related to gift-giving and Schwartz’s (1992) Personal Values Theory is the main contribution of this study. The proposal and testing of an integrative model of these two theories will broaden the knowledge generated by the few studies already done.

This paper is structured in five sections beyond this introduction. The next section presents a review of the literature on gift-giving and Personal Values Theory. Based on these theories, the third section presents the research model used in this paper. In the following sections, the methodological procedures are presented, the data is analyzed and final considerations are made. In the last section, theoretical and practical implications are discussed and further studies suggested.

2. Literature review

This section presents the conceptual basis used to support and guide the paper. The objective was to address studies related to the themes of gift-giving and personal values. First, Gift-giving Theory will be detailed, with a primary focus on efforts made to understand and model consumer behavior in all phases of gift-giving. Following this, Personal Values Theory will be presented. Finally, studies that relate the two theories with the aim of predicting behavior will be addressed.

2.1. The gift-giving act

The first studies involving the behavior of consumers in the act of gift-giving date back to the 1970s, including noteworthy research carried out by Belk (1976). In it, the author develops an exploratory analysis, pointing to a gap in consumer behavior studies at the time. Belk (1976) identified four gift-giving elements, namely the person who gives the gift, the gift itself, the person who receives the gift and the situational conditions. For him, individuals, families or organizations can take on both the roles of gift-givers or receivers. The gift may vary greatly, being that it can be given in cash, acquired as a good or service, or even donated, as in the case of organs and blood. However, the situational conditions vary according to the occasion upon which the gift is given.

Among gift-giving functions, Belk (1976) highlights communication, social exchange and economic exchange. Communication is made possible by the perceptions embedded in the gift and the images that the giver possesses and wishes to communicate about himself and the gift. Social exchange occurs through reciprocity of the trade between the giver and the recipient, having an important impact on the social relationship between both parties. Economic exchange occurs through the pursuit of the giver’s self-satisfaction, and the resultant reciprocity from the person who receives the gift.

In later studies, Sherry (1983) complemented Belk’s studies from an anthropological perspective. The author proposed a model where gift-giving is composed of three phases: the gestation (of antecedent factors), gift presentation or delivery and reformulation. During gestation, the giver is encouraged by a situation (for example, Christmas parties or Valentine’s Day), to conduct research into a gift, which will then be transported from the conceptual world to the material world. At the presentation stage, the ritual of delivering the gift occurs, which generally inverts the roles, so the giver becomes the receiver and vice-versa, since the one who receives the gift must now give a response to the gift-giver. This response is given by the decoding of the symbolic content of the gift and by the actual response, when the one who receives the gift infers the giver’s intention and formulates his judgment about the gift. In the last phase, reformulation, the gift is given a destination by the recipient (utilization, exposition, storage, trade or rejection), and pre-existing relationships are then restructured.

Sherry (1983) affirms that the physical and psychological effort in choosing, preparing and giving a gift attributes value to the object. The gift becomes a representation of the giver, who gives a portion of himself to the recipient. Flynn and Adams (2009) reinforce this, suggesting that the giver’s primary concern should be commitment to finding something that delights the recipient, regardless of the price.

Obligation is another typical characteristic of the gift-giving act. In many cases, obligation can be the central rea-son for buying the gift, once there is the feeling that not giving a gift is inappropriate, such as not getting a Valentines gift for one’s partner (Davies et al., 2010). Pépece (2000) posits that the feeling of being obliged to give a gift can be based on moral or religious matters, on the necessity of recognizing and maintaining a certain status hierarchy, on the necessity of establishing or maintaining peaceful relations between individuals, or simply on the expectation of reciprocity.

Sherry (1983) identifies two types of motivations related to the feeling of pleasure. The first, called altruistic, occurs when the giver seeks to maximize the recipient’s feeling of pleasure as he or she receives the gift. The second, called agnostic, aims to maximize the feeling of pleasure experienced by the giver himself. Otnes, Kim and Lowrey (1992), on the other hand, mention some characteristics of gift choices that would make the process less pleasant: 1) the perception that the recipient does not want or need any kind of gift; 2) the fear of giving something that displeases; 3) the existence of extremely different tastes and interests between the giver and the receiver; 4) lack of familiarity with the receiver; 5) the perception of physical or personality limitations of the receiver; 6) limitations of the gift-giver such as financial constraints; 7) concerns about the impossibility of reciprocating the received gift with something of com-parable value; 8) conflict between giver and receiver; 9) facing a choice previously made by the receiver.

Davies et al. (2010) point out two influencing factors in gift-giving that have already been demonstrated in the literature: culture and gender. The culture in which the gift is given takes into account the quality of the relationship between the parties, in addition to the social context in which they live. Moreover, gender, commonly seen as an important factor in consumer behavior, is even more significant in the gift exchange (Bodur & Grohmann, 2005).

Studies by many authors (Cheal, 1987; Cleveland, Babin, Laroche, Ward & Bergeron, 2003; Nepomuceno, Saad, Stenstrom, Mendenhall & Iglesias, 2016) have analyzed the gender issue and identified a greater involvement of women in the act of gift giving. Cheal (1987), for example, argues that this difference is due to the greater concern of women in demonstrating love, care and attention to others. For the authors, it is common sense in some cultures that purchasing a gift is essentially a female role, leading many women to consider the act of giving something extremely important in the socialization process.

As observed, the act of giving can involve feelings of both pleasure and obligation, and there are significant differences between individuals both in the effort involved in choosing and also in the frequency of gift-buying. These attitudes and behaviors can be influenced, among other aspects, by culture and gender, the latter being mainly related to the giver. Since the gender factor is something tangible and simple to measure, it is necessary to find a way to evaluate the impact of culture in the process.

Davies et al. (2010) point out that there have been very few attempts to apply consumer behavior models in the context of gift giving, and even fewer cases where such models have been empirically tested. Although there are many perspectives to understand the act of gift giving, the personal values perspective presents itself as a fruitful theoretical lens for such a proposal. Borg et al. (2015) argue that Personal Values Theory would be able to explain and predict the collective behaviors of individuals within the same culture. This topic will be covered in the next section.

2.2. Personal values theory

Values have been the focus of studies in several academic fields, and two distinct approaches have been identified in marketing studies. The first of these is the instrumental evaluation of values, which studies the chain of meanings that connects values with behaviors (Amatulli, Pino, De Angelis, & Cascio, 2018). In this approach, consumption is understood as a goal-oriented phenomenon (values) that are achieved through the consumption of products with specific characteristics.

However, the value hierarchy approach considers that the value system of an individual or group is a psychographic or cultural characteristic that influences the direction of their behaviors and/or their way of acting (Munson & McQuarrie, 1988). This approach analyzes the profile of consumers using an inventory of general human values, as proposed by Rokeach (1973) and Schwartz (1992). The value hierarchy was chosen as the best alternative for conducting quantitative studies, allowing the measurement and comparison of values among groups of individuals, as well as the analysis of their relation to certain behaviors (Munson & McQuarrie, 1988).

Personal values can be used as standardized criteria in explaining consumer behaviors. There is a tendency for these values to be limited to a restricted set and to remain stable over time (Kamakura & Mazzon, 1991). Because of this, personal values have already been measured with different scales and for different marketing purposes, such as the distinction of cultural groups and the definition of consumer stereotypes, analysis of subcultures and social classes, as well as market segmentation (Munson & McQuarrie, 1988).

Torres, Schwartz and Nascimento (2016) point out that Rokeach is responsible for the development of the first empirical study in psychology to measure personal values. For Rokeach (1973) values play a central role in the study of human behavior: the concept of values makes it possible to unify the apparently diverse interests of all sciences related to human behavior.

Following Rokeach, there have been several efforts to measure individuals’ value priorities, with the purpose of understanding the motivations that lead them to particular attitudes and behaviors according to environmental demands (Torres et al., 2016). Schwartz's Theory of Personal Values (1992) is the one that has gained greatest attention from researchers in this area (Torres et al., 2016).

Schwartz (1992) proposes that values (1) are conceptions or beliefs, (2) belong to desirable states or behaviors, (3) transcend specific situations, (4) guide the selection or evaluation of behaviors and events, and are ordered by relative importance. According to the author, values are motivational constructs that assume a conscious character and have the function of responding to the three universal demands or tasks of human existence: biological needs, social interaction and survival, and well-being of the collective.

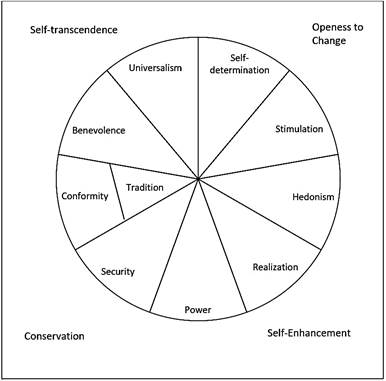

Schwartz (1992) proposed a unifying theory of personal values where motivational goals would be substantive and would organize the content of values, communicating three inherent needs of any human being: biological needs, coordinated social interaction, and the functioning and maintenance of groups. These values would be included in ten categories, called motivational types (or basic values), which differ according to the motivational content represented, such as self-determination, stimulation, hedonism, realization, power, safety, conformity, tradition, benevolence and universalism.

The analysis of these values made it possible to identify relations of compatibility and conflict between motivational types, resulting in a structure in which adjacent types share motivational emphases, whereas those in opposition indicate conflicting goals, reflecting a motivational continuum resulting in a circular structure (Sambiase, Teixeira, Bilsky, Araujo, & Domenico, 2014). The circle is also divided into four broad categories, called self-transcendence, conservation, self-promotion, and openness to change. According to Borg et al. (2015) these four categories constitute the most general motivations that justify adherence to and achievement of certain motivational values.

Figure 1 graphically demonstrates the circular structure proposed by Schwartz (1992), where the antagonism and the proximity between different values are highlighted.

For Torres et al. (2016), as conceived by Schwartz, human values are important constructs in the set of psychosocial concepts considered central to the prediction of attitudes and behaviors, including for the understanding of phenomena of interest in the study of the social and human sciences. This characteristic led to the emergence of several scales for the measurement of personal values.

Among the proposed scales, PVQ-40 stands out because it has been validated in several countries, including Brazil (Tamayo & Porto, 2009). PVQ-40 was developed by Schwartz to simplify the field research process, reducing the required response time, facilitating the understanding of questions and using projective questioning about behaviors and concrete postures before different aspects of life in society. Thus, it is more recommended for research with less-educated adults, children and adolescents (Sambiase et al., 2014) and suitable for the present study.

2.3. Personal values and the gift-giving act

Kamakura and Mazzon (1991) argue that personal values have great potential for explaining behaviors. Values can be used as standardized criteria, since they tend to be limited to a restricted set and are stable over time. In this way, it becomes possible to compare the values and the analysis of their relation with certain behaviors of individuals (Munson & McQuarrie, 1988).

An important mediator of this relationship between personal values and behavior is attitude. The relationship between attitude and behavior is among the most studied topics in marketing and psychology. Matos, Ituassu and Rossi (2007) define attitude as being a predisposition that leads to a consistent favorable or unfavorable behavior towards a given object. The authors consider that attitude is highly correlated to the intention of the individual, which, in turn, allows for a prediction of their behavior.

Nepomuceno and Porto (2010) reinforce this view by identifying evidence in the literature that personal values can influence attitudes, which in turn influence consumer behavior.

Since gifts are agents of exchange and social communication, in addition to being used to establish and maintain relationships, it is possible to conclude that the gift is in some way linked to the individual's personal values (Lowrey, Otnes, & Robbins., 1996; Ferrandi et al., 2015). Despite this, studies on the impact of values on consumption only began to be applied in the context of gift-giving from the 1990s onwards (Lowrey et al., 1996; Ferrandi et al., 2015).

Beatty, Kahle and Homer (1991) presented one of the pioneering studies in this area. The authors suggested that groups of people with certain values have a greater tendency to engage in specific behaviors than others. Considering their empirical study, people with a certain set of values have consistent attitudes and behaviors even among different cultures and genders.

Later, Beatty, Kahle, Utsey and Keown (1993) proposed that the purchase of non-compulsory gifts occurs in response to the priorities of an individual's values. From a study involving people from the United States and Japan, the authors concluded that values influence the amount of non-mandatory gifts purchased, regardless of gender or culture variations. The same did not occur, however, for the effort employed in the choice of gift, since women reported to have engaged more effort in this process.

More recently, Aung, Zhang, and Teng (2017) studied the behavior of bi-cultural givers by analyzing the impact of Chinese cultural values on the choice of gifts by women who had migrated to Canada. For the authors, the distinct decision-making processes, their patterns of consumption, and their gifting behavior may be perceived as a direct result of Chinese values. These values are motivational elements that can play a crucial role during gift choice.

From the aforementioned studies, it can be said that personal values can be promising variables for understanding consumers' attitudes and behaviors in the act of giving. By approaching the hierarchy of values, it becomes possible to decipher their way of acting and predict the direction of their behaviors (Munson & McQuarrie, 1988). In the following section a model relating to Gift Giving theory and Personal Value Theory will be proposed, assuming that personal values are influential factors in the gift-giving act.

3. The proposed model

The feeling of pleasure in the gift-giving act can be un-derstood as a satisfying feeling when the act is experienced, viewed as something fun, a noble expression of love or commitment (Nguyen & Munch, 2011). Wolfinbarger and Yale (1993) consider that a positive attitude towards the giving act primarily arises from a hedonic motivation. Considering that motivation and values are closely related (Beatty et al., 1991), the motivation stemming from the pleasure at gift giving can be associated with the value of hedonism. This value derives from the pleasure coming from the satisfaction of needs (Schwartz, 1992). With this view in mind, the following hypothesis is formulated: “H1 - Hedonism has a positive effect on the pleasure of gift-giving.”

Belk (1979) proposes that the feeling of pleasure is greater when the giver feels free to make the purchase, rather than having his choice limited by a specific request from the giver. The observation that restraint of choice can reduce pleasure leads one to believe that there is a positive relationship between pleasure and the personal value of self-determination. According to Schwartz (1992), self-determination is defined mainly by independent thinking and free action in relation to choices, creation and exploitation. As such, the following hypothesis is formulated: "H2 - Self-determination has a positive effect on the pleasure of gift-giving."

Nguyen and Munch (2011) define the obligation to give a gift as the perception of a task, a motivation with the sense of stress when buying a gift. Giving gifts to family members, for example, has a connotation of moral obligation (Komter & Vollebergh, 1997). On occasions such as birthdays or holidays, the sense of obligation is more closely linked to social or religious norms (Davies et al., 2010; Pépece, 2000; Wolfinbarger & Yale, 1993). In the latter case, it is possible to propose a relationship between the feeling of obligation and the value of tradition. According to Schwartz (1992), the value of tradition is seen as the search for subordination to socially imposed customs, dealing especially with aspects related to religion and culture. Considering that customs and traditions are related to socially imposed commitments, the following hypothesis is formulated: "H3 - Tradition has a positive effect on the obligation to give a gift".

In addition to being based on moral and religious issues, the sense of obligation to give may also be linked to the need for recognition and maintenance of a status hierarchy (Pépece, 2000). This necessity makes it possible to relate the obligation with the personal value of realization. Maintaining the status hierarchy can be associated with the personal value of power.

For Schwartz (1992), realization is the value that seeks personal success by demonstrating competence according to social standards. Individuals looking for realization demonstrate their competence according to prevailing cultural patterns, aiming at social recognition. The next hypothesis can therefore be formulated as: "H4 - Realization has a positive effect on the obligation to give a gift".

Power is the pursuit of social status and prestige through control and domination over people and resources, striving for authority, wealth, social power, preservation of the public image and social recognition (Schwartz, 1992). Unlike the value of realization, which seeks to demonstrate skills recognized by society, power emphasizes the recognition and preservation of a dominant position through the hierarchy of social status. For these reasons, the following hypothesis is formulated: "H5 - Power has a positive effect on the obligation to give a gift".

The sense of obligation may be associated with the need to establish or maintain peaceful relationships with other individuals (Pépece, 2000). This need can be understood as the quest for security. Schwartz (1992) defines security as the search for harmony and stability in society, in terms of interpersonal relationships and within the individual themselves. In light of this, the following hypothesis is formulated: "H6 - security has a positive effect on the obligation to give a gift".

When evaluating the sense of obligation to give and its relation to moral or religious issues, aside from the motivations imposed by society on account of the occasion (Pépece, 2000), it is possible to perceive a contradiction in relation to the value of self-determination. As previously noted, for Schwartz (1992), self-determination aims at enabling independent thinking and free action in relation to choices, creation and exploration. It is reasonable, therefore, to propose that the search for autonomy given by self-determination would be contradictory to obligation, leading to the next hypothesis: "H7 - Self-determination has a negative effect on the obligation to give a gift."

Nepomuceno and Porto (2010) affirm that there is evidence in the literature that personal values can influence attitudes, which in turn will influence consumer behavior. The proposed theoretical model also seeks to validate this relationship between attitudes (Pleasure and Obligation) and behaviors (Effort and Frequency).

Obligation is seen by several authors as one of the main motivators for the exchange of gifts (Nguyen & Munch, 2011; Wolfinbarger & Yale, 1993; Komter & Vollebergh, 1997; Davies et al., 2010). In this sense, the next hypotheses are formulated: "H8 - The obligation to give a gift has a positive effect on the effort expended in giving it" and "H9 - Obligation to give a gift has a positive effect on the frequency of gift giving."

Some authors consider pleasure as an important motivator for gifting (Sherry, 1983; Ferrandi et al., 2015). Wolfinbarger and Yale (1993) go further, and consider that a positive attitude toward giving is primarily due to a hedonic motivation. With this in mind, the following hypothesis is formulated: "H10 - The pleasure of gift-giving has a positive effect on the effort expended in gift-giving" and "H11 - the pleasure in gift giving has a positive effect on the frequency of gift giving."

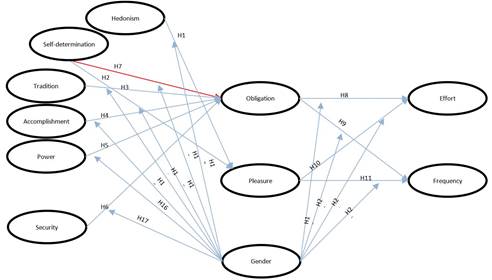

Finally, Beatty et al. (1991) suggest that gender does not influence the relation between personal values and the gift-giving act, even when this relationship is observed between different cultures. On the other hand, the literature on gift giving points to many studies where gender is an influential factor in the attitudes and behaviors of consumers (Davies et al., 2010; Pécece, 2000; Cheal, 1987; Cleveland et at., 2003; Nepomuceno et al., 2016). It is therefore suggested that: “A gender moderator effect exists in all hypothetical relationships previously proposed”, as indicated by hypotheses H12 to H22, illustrated in Figure 2 representing the theoretical model to be validated in this study.

4. Methodology

In order to verify the hypotheses presented, a field survey was carried out. The questionnaire was composed of questions related to personal profiles, as well as questions about gifts and personal values.

The pleasure and obligation scales contained four items each (Nguyen & Munch, 2011), while the frequency and effort scales contained three items each (Beatty et al., 1991). As these were scales not yet used in Brazil, the process of translation and reverse translation from English to Brazilian Portuguese was carried out, and the original Likert scale with eleven points was used, ranging from "0-totally disagree" to "10- I totally agree". Personal values were verified using the PVQ-40 scale, translated and validated by Tamayo and Porto (2009). In this case, the original Likert scale with six points was used, with "0 - It does not look anything like me" and "5 - It looks a lot like me".

The questionnaire was submitted to two pre-tests before being applied with the final sample. The research universe comprised individuals over the age of 18 from all Brazilian states, of both sexes, who have access to the internet.

The collection was done through an online tool commercialized by the research company OpinionBox. This tool allowed the collection of answers from people who registered voluntarily in exchange for micro rewards (eg.: mobile phone credits) and who underwent a process of validation and auditing.

Online data collection through a panel of respondents for quantitative research has increased greatly in several areas of research. The use of online panels has three main advantages: quick data collection, lower unit cost of data collection, and sampling efficiency. Such evolution and application of online panels was made possible by the exponential growth of the internet (Callegaro et al., 2014).

The final sample consisted of 1,085 respondents, stratified by sex, age, education, income and region, seeking to represent the demographic division of the Brazilian population.

In the data analysis phase, we used exploratory factor analysis and structural equation modeling as techniques to validate the scales and the proposed theoretical model. Structural equation modeling was performed using the PLS (Partial Least Squares) approach. For data treatment, the software R (version 3.4.1) and Minitab Express (version 1.5.1) were used.

It should be noted that, due to the procedures adopted in the collection, no missing data was observed. There were also no atypical observations (outliers).

5. Results

The data collection stage was carried out from the 4th to the 10th of July, 2017. Table 1 presents the characterization of the respondents who participated in the research.

Table 1 shows that the sample covered all age groups, marital statuses, socioeconomic classes and states in Brazil. It appears that the majority (58.71%) of the respondents identified themselves in the questionnaire as being female, while the rest (41.29%) presented themselves as being male. It is also observed that the most present age groups were between 30 and 39 years old (39.35%) and between 40 and 49 years old (29.68%). The age group least represented in the survey was between 20 and 29 years old, corresponding to only 3.5% of the respondents.

Table 1 Sample characterization

| Variables | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 637 | 58.71% |

| Male | 448 | 41.29% | |

| Age | Under 20 years old | 53 | 4.88% |

| Between 20 and 29 years old | 38 | 3.50% | |

| Between 30 and 39 years old | 427 | 39.35% | |

| Between 40 and 49 years old | 322 | 29.68% | |

| Between 50 and 59 years old | 152 | 14.01% | |

| Over 59 years old | 93 | 8.57% | |

| Socioeconomic Classification | AB | 276 | 25.44% |

| CDE | 809 | 74.56% | |

| Marital Status | Married | 557 | 51.34% |

| Divorced | 52 | 4.79% | |

| Single | 464 | 42.76% | |

| Widow | 12 | 1.11% | |

| Region | Center-West | 73 | 6.73% |

| North | 79 | 7.28% | |

| Northeast | 235 | 21.66% | |

| South | 155 | 14.29% | |

| Southeast | 543 | 50.05% |

Source: own elaboration.

In the treatment of the data, Exploratory Factor Analysis was used to create the indicators of pleasure, obligation, effort, frequency, self-determination, stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power, security, compliance, tradition, benevolence and universalism that represented each of the constructs. Based on the results, it was not necessary to exclude any item from the constructs, as all factor loads were satisfactory with values above 0.60.

To verify the validity of the set of indicators for each construct to accurately represent its respective concept, convergent validity, reliability and dimensionality were evaluated. The results can be seen in Table 2.

From the data available in Table 2, it appears that there was convergent validation in all constructs, since they all had AVEs greater than 0.40. The Cronbach's Alpha (A.C.) or Composite Reliability (C.C.) indicators also showed values above 0.60 in all constructs, therefore all constructs reached the required levels of reliability. This also showed that the adjustment of the Factor Analysis was adequate, since all constructs presented KMO values equal to or greater than 0.50. Finally, it is observed that all constructs were one-dimensional.

Table 2 Reliability, convergent validity and dimensionality of constructs

| Constructs | Items | C.A.¹ | C.C.² | Dim.³ | AVE4 | KMO5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleasure | 4 | 0.828 | 0.838 | 1 | 0.683 | 0.789 |

| Obligation | 3 | 0.745 | 0.782 | 1 | 0.665 | 0.670 |

| Effort | 3 | 0.708 | 0.761 | 1 | 0.633 | 0.671 |

| Frequency | 4 | 0.618 | 0.713 | 1 | 0.479 | 0.658 |

| Self-determination | 4 | 0.648 | 0.723 | 1 | 0.493 | 0.709 |

| Stimulation | 3 | 0.661 | 0.736 | 1 | 0.598 | 0.660 |

| Hedonism | 3 | 0.711 | 0.761 | 1 | 0.634 | 0.675 |

| Accomplishment | 4 | 0.717 | 0.755 | 1 | 0.542 | 0.755 |

| Power | 3 | 0.628 | 0.725 | 1 | 0.579 | 0.594 |

| Security | 5 | 0.686 | 0.734 | 1 | 0.444 | 0.712 |

| Conformity | 4 | 0.622 | 0.714 | 1 | 0.480 | 0.616 |

| Tradition | 4 | 0.536 | 0.672 | 1 | 0.421 | 0.655 |

| Benevolence | 4 | 0.737 | 0.778 | 1 | 0.578 | 0.761 |

| Universalism | 6 | 0.804 | 0.808 | 1 | 0.514 | 0.854 |

1Cronbach’s Alfa; 2 Composed Reliability; 3 Dimensionality; 4 Extracted Variance; 5Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin’s sample suitability measure.

Source: own elaboration.

Based on these results, it can be said that the present study offers an additional contribution to future works on the theme, as the constructs related to the act of gifting were found to be valid and reliable, in addition to the paper reinforcing the quality of the scales used, which could be applied in other contexts.

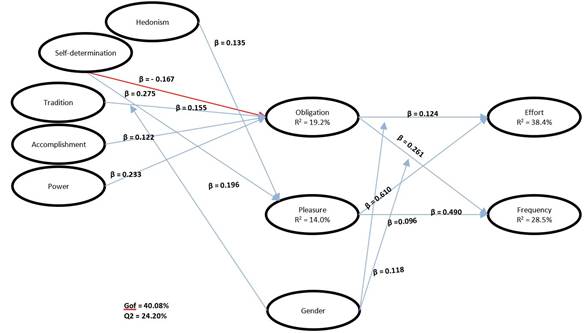

The present study proposes a model to verify the hypotheses previously discussed. Thus, in order to validate this model and verify the correlations between the constructs of personal values and gift giving, structural equation modeling was used, using the PLS approach (Partial Least Squares). In assessing the quality of the models' fit, R2 and GoF were used. To assess the size of the effect of the predictor construct, Cohen's f2 was used. To assess predictive relevance, the Q2 statistic was used. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Structural Model

| Endogenous | Exogenous | β | F² | E.P.(β)1 | Value-p | Q² | R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleasure | Self-determination | 0.275 | 0.042 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 7.0% | 14.0% |

| Hedonism | 0.135 | 0.012 | 0.036 | 0.000 | |||

| Obligation | Self-determination | -0.167 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 8.7% | 19.2% |

| Accomplishment | 0.122 | 0.009 | 0.037 | 0.001 | |||

| Power | 0.233 | 0.041 | 0.035 | 0.000 | |||

| Tradition | 0.155 | 0.011 | 0.029 | 0.000 | |||

| Tradition x Gender | 0.196 | 0.042 | 0.029 | 0.000 | |||

| Effort | Pleasure | 0.610 | 0.365 | 0.024 | 0.000 | 23.8% | 38.4% |

| Obligation | 0.124 | 0.013 | 0.030 | 0.000 | |||

| Obligation x Gender | -0.118 | 0.012 | 0.030 | 0.000 | |||

| Frequency | Pleasure | 0.490 | 0.227 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 16.7% | 28.5% |

| Obligation | 0.261 | 0.028 | 0.033 | 0.000 | |||

| Obligation x Gender | -0.096 | 0.006 | 0.033 | 0.003 |

¹ Pattern Error; GoF = 40.08%. Q2 = 24.20%.

Source: own elaboration.

Based on Table 3, it is possible to make some considerations regarding each dependent variable.

There was a significant (p-value = 0.000) and positive (β = 0.275) influence of self-Determination on pleasure. There was also a significant (p-value = 0.000) and positive (β = 0.135) influence of hedonism on pleasure. The self-determination and hedonism constructs were able to explain 14.0% of pleasure.

As for the obligation variable, there was a significant (p-value = 0.000) and negative (β = -0.167) influence of self-determination on obligation. There was also a significant (p-value = 0.001) and positive (β = 0.122) influence of accomplishment on obligation. There was also a significant (p-value = 0.000) and positive (β = 0.233) influence of power over obligation. In females, there was a significant (p-value = 0.000) and positive (β = 0.155) influence of tradition on obligation. Therefore, the greater the level of tradition, the greater the obligation tends to be. In males, the impact β= 0.155 increases by 0.196, this increase being significant (p-value = 0.000). Therefore, both impacts were positive, with the male gender being greater. It appears that the constructs self-determination, achievement, power, tradition and tradition x gender were able to explain 19.2% of obligation.

There was a significant (p-value = 0.000) and positive (β = 0.610) influence of pleasure on effort. It is also noted that in females, there was a significant (p-value = 0.000) and positive (β = 0.124) influence of obligation on effort. In males, the impact of β = 0.124 reduces to -0.118, this reduction being significant (p-value = 0.000). Therefore, both impacts were positive, with the female gender being greater. It is observed that the constructs pleasure, obligation and obligation x gender were able to explain 38.4% of effort.

Regarding the frequency variable, it is worth mentioning that there was a significant (p-value = 0.000) and positive (β = 0.490) influence of pleasure on frequency. In females, there was a significant (p-value = 0.000) and positive (β = 0.261) influence of the obligation on frequency. In males, the impact of β = 0.261 reduces to -0.096, with a significant reduction (p-value = 0.003). Therefore, both impacts were positive, with the female gender being greater. It appears that the plea-sure, obligation and obligation x gender constructs were able to explain 28.5% of frequency.

It should also be noted that the model had a GoF of 40.08% and an overall predictive relevance of 24.20%.

The hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H4, H5 and H7, proposed for the relation between personal values and attitudes to gift-giving, were confirmed. The only exception was hypothesis H6. We just could not verify the effect of the personal value of security. These results corroborate the studies of Beatty et al. (1991), who proposed that individuals engage in behaviors such as the exchange of gifts with the aim of satisfying their values.

It was not possible to validate hypothesis H6 which states that secutiry would be one of the motivating factors of the obligation to give (H6). According to Schwartz (1992), individuals who value security seek the harmony and stability of interpersonal relationships. Pépece (2000), on the other hand, states that people who seek to maintain peaceful relationships with other individuals have a greater sense of obligation to give. Although they seem to be aligned, the present study pointed out that the relationship indicated by Pépece (2000) was not enough to explain the feeling of obligation, indicating an important gap between theory and the data analyzed.

The hypotheses H8, H9, H10 and H11, indicating the positive effect of attitudes (obligation and pleasure) on behaviors (effort and frequency) in the act of giving, were all confirmed. This result corroborates the view of several studies in the area of marketing and psychology, which identify which attitudes influence consumer behavior (Matos et al., 2007; Nepomuceno & Porto, 2010).

Moreover, the moderating effect of gender was validated in the theoretical model only for the relationship between tradition and obligation (H14), obligation and effort (H19) and obligation and frequency (H20). The effect found for the relationship between tradition and obligation was always positive, regardless of gender. As such, the greater the value of tradition, the greater the feeling of obligation to give. This result confirms the observation made by Beatty et al. (1991), who identified that the association between personal values and behaviors occurs independently of gender. The fact that the positive effect is greater for men also corroborates a study by Pépece (2000), who showed that they perceive a greater sense of obligation than women when the gift is linked to a certain special occasion, usually defined by the tradition of the local culture.

Gender moderation in terms of obligation, effort and frequency relationships also showed results in accordance with Gift Giving Theory, pointing to a greater involvement of women in the exchange of gifts (Cheal, 1987; Cleveland et al., 2003). This difference, however, was not sufficient to change the sense of the relations, maintaining a positive effect regardless of gender.

For Beatty et al. (1991), individuals who value their relationships with others are likely to try harder and give gifts more often. Women stand out in this group, since they consider gift giving extremely important in the socialization process. Cheal (1987) argues that this difference is due to the greater concern of women in showing love, care and attention to their neighbors. The sense of obligation in women's gifting would be further reinforced by the common sense in some cultures that believe that the purchase of gifts is essentially a female activity.

The Stone-Geisser indicator confirms the predictive validity of the relationships predicted in the model, since all the results (Q²) are higher than zero. In the analysis of the Pearson Determination Coefficients (R²), all effects are considered relevant (above 14%).

The structural model validated in this study is illustrated in Figure 3.

6. Conclusion

The objective of this study was to propose and validate a model that allows an analysis of whether personal values influence the attitudes and behaviors observed during the act of gift giving, while also considering the role of gender in these relations. A quantitative approach was used surveying 1,085 Brazilian consumers and structural equation modeling was used to test the proposed theoretical model. Aside from gender as a moderating variable, this model also considered the relationship between attitudes and behaviors in the act of gift-giving.

It is concluded that the proposed model was validated, and that all constructs were one-dimensional, having also verified the validity and reliability of the scales used. Among the 22 hypotheses presented, 13 were not refuted, demonstrating the relevance of the proposed model.

Among the 7 hypotheses regarding the relationship between personal values and attitudes to giving, 6 were not refuted. The only exception was the hypothesis that the personal value of security would be one of the motivating factors for the feeling of the obligation to give.

The hypotheses related to the positive effect of attitudes (obligation and pleasure) on behaviors (effort and frequency) when giving gifts were all confirmed. This result reinforces the understanding that attitudes influence consumer behavior.

On the other hand, among 11 hypotheses regarding the moderating effect of gender, only 3 hypotheses were confirmed. The results indicated a greater involvement of women in the exchange of gifts. This difference, however, was not enough to change the meaning of the relationships, maintaining a positive effect regardless of gender. It was possible to verify that the values of tradition, realization, power and self-determination influenced the feeling of the obligation to give, and only the latter had a negative effect. Furthermore, the values of hedonism and self-determination produced a positive effect on the pleasure of gift-giving. All effects presented the same meaning for men and women, varying only in their intensity in the case of the relationship between tradition and obligation (more positive for men). In other words, from this study it can be affirmed that personal values can be used to predict gifting behavior independently of gender.

The connection between attitudes and behaviors was also validated, since both obligation and pleasure had a positive influence on the effort and frequency of giving (with pleasure having greater weight). Here as well, moderation by gender was not enough to change the meaning of these relationships, although it did reduce the effects for men in the case of the influence of obligation, effort, and frequency.

As part of the process for the validation of the theoretical model, scales were used to measure personal value constructs and gift-giving. These scales have undergone the recommended procedures, such as translation and reverse translation, as well as pre-testing, presenting appropriate validity and reliability, thereby representing a contribution to future studies related to this subject.

It was also possible to validate a scale of personal values with a relatively large and heterogeneous sample of consumers. Individuals of both sexes were surveyed, covering all age groups, civil states, socioeconomic classes and Brazilian states, something apparently unheard of in studies on personal values in Brazilian scholarship.

In general, the study offers important contributions to the field of marketing. The findings filled an important gap in studies of gift giving, increasing knowledge in this domain by incorporating personal values in the prediction of the attitudes and behaviors of consumers.

For the field of management, the first contribution was the identification of personal values that motivate positive feelings and desired behaviors in consumers. It can be noted that five values have a direct relationship with the act of giving, namely tradition, realization, power, self-determination and hedonism. In addition, self-determination and hedonism are the values that influence behavior the most, since they are the only ones to have positive effects on pleasure (the attitude with greatest influence on effort and frequency).

Although not characterized as a probabilistic sample, the collected data set composes an important database of Brazilian consumers. This database can be used for in-depth analyses of personal values in various strata of society, as well as facilitating new research that seeks to validate theoretical concepts on this subject, and opening possibilities for new research that seeks to validate the area’s theoretical concepts.

Another suggestion would be to carry out studies that investigate other dimensions addressed in the gift-giving literature, such as the relationship with the gift, the occasion, the religion of the giver, and the price of the gift (Pépece, 2000). Such analyses will enrich the understanding of the factors that influence consumer behavior in the exchange of gifts.

Finally, the fact that the relationship between the personal value of security and the feeling of obligation in gift-giving has not been confirmed points to possibilities for future studies. When comparing the results found in the research with the literature, we were able to identify a gap that can be analyzed in other contexts.