1. Introduction

Responsible Leadership (RL) is defined as a “relational and ethical phenomenon, which occurs in social processes of interaction with those who affect or are affected by leadership and have a stake in the purpose and vision of the leadership relationship” (Maak & Pless, 2006, p. 103). Despite being a relatively new area, research on RL has in-creased over the past decades1. Scholars have examined, for example, the different definitions of a responsible leader (Maak & Pless, 2006; Pless, 2007), the responsible leader’s emergence and the actions that characterize them (Pless, 2007), the leader responsibilities (Miska & Mendenhall, 2018; Pless et al., 2012; Voegtlin et al., 2012; Waldman et al., 2020), the language that distinguishes those organizations focused on social responsibility (called B Corp) and the presence of RL in them against those organizations that do not have it (Stryker & Stryker, 2020), and the situations and factors that favor the development of responsible leaders (Kovar & Simonsen, 2019; Pless et al., 2011; Steyn & Sewchurran, 2021). The last line of research is beginning to get greater scholarly and practitioner attention (Pless & Maak, 2022); however, several questions about RL remain to be addressed.

Although some studies have recently tested the RL construct or some of the proposed theoretical models in an empirical manner (through quantitative research) (cf. Voegtlin et al., 2020), the extant literature on RL is still theoretical and normative (e.g., Doh & Quigley, 2014; Miska & Mendenhall, 2018; Stahl & Sully de Luque, 2014; Waldman & Balven, 2014). Miska and Mendenhall (2018) reviewed the theoretical foundations and methodological approaches of research on RL. They identified three levels of analysis (micro, meso, and macro) and concluded that, in recent years, research has moved from micro-level analysis (focused mainly on the leader) to a multi-perspective (focused on the leader, the organization, and the context). Waldman and Balven (2014) presented an overview of divergences in the RL literature. They identified five future areas of research: RL processes and outcomes, RL stakeholder priorities, RL training and development, RL globalization and macro-level forces, and RL measurement and assessment.

Recent reviews, and some other theoretical models (e.g., Stahl & Sully de Luque, 2014), have revealed that the context in which the leaders interact (social, economic, and political) is crucial to understanding the RL phenomenon. However, such studies have mainly focused on the European and North American contexts (Maak et al., 2014; Waldman et al., 2006) and paid scant attention to RL in developing economies. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only one study has tried to assess the competencies of responsible leaders world-wide considering multiple contexts or regions (Muff et al., 2022). Studies based on the European and North American contexts are relevant because they allow a broader understanding of the RL phenomenon; however, research suggests that the situational context and the leadership characteristics of developing economies, such as Latin America, differ from them (see Aguinis et al., 2020; Davila & Elvira, 2012; Nicholls-Nixon et al., 2011). Thus, as Pless et al. (2021) point out, “while significant advances have been made in recent years towards a better understanding of the concept, a gap exists in the understanding of responsible leadership in emerging countries.” (p. 1). This makes more sense if we consider that in the most recent study assessing multiple regions or social contexts, the participation of the Latin American population in the sample was only 1% (see Muff et al., 2022).

As Aguinis et al. (2020) argued, management research rooted in developed economies tends to assume specific characteristics such as the presence of stable, reliable, and formal institutions. However, these situational assumptions do not represent developing economies. Research suggests that Latin American institutions are less efficient than those of other regions (Aguinis et al., 2020; Nicholls-Nixon et al., 2011); this one faces larger institutional voids, weak market infrastructures, inequalities in income distribution, and political and economic conditions that create problems to meet the broader population needs. Furthermore, the constant economic and political instability influences this context; political parties impose their agendas and affect how leaders engage in and behave toward general societal problems such as education and healthcare (Vassolo et al., 2011).

Few studies have focused on more unfavorable contexts such as developing countries (Pless et al., 2021; Stahl et al., 2016; Witt & Stahl, 2016). Then, what role does the Latin American context play in the development of RL? How do responsible leaders develop in such adverse conditions? This study addresses these questions by reviewing RL research in Latin America. As recently highlighted by Aguinis et al. (2020), research focused on these regions is critical “to build and test theories with implications for important societal challenges” (p. 2).

Understanding RL development in that context could be fundamental for scholars and practitioners. For scholars, understanding how RL develops in more unfavorable contexts could help to (1) develop a broader conceptualization of RL that also includes the possible differences between developed and developing economies; (2) advance a more comprehensive research agenda that also accounts for the contextual characteristics; and (3) promote research insights in such unfavorable contexts. For practitioners, accurate knowledge of the development of RL in a more adverse context could help create better leadership initiatives within business schools (e.g., service-learning education programs, see Rook & McManus, 2020) and leadership development initiatives within organizations (e.g., the Project Ulysses at PricewaterhouseCoopers, see Pless et al., 2011; or the Corporate Service Corps at IBM, see Colvin, 2009) and within leadership multi-organizational initiatives (e.g., UN Global Compact, 2020). Finally, organizations (e.g., multinationals) could gain insights into the context of leadership development and its importance during their talent management practices and selection processes.

As such, the purpose of this article is threefold: (1) to review the extant research on RL that may provide insights into the understanding of the phenomenon’s development even under the challenging conditions of developing economies; (2) to review the literature on RL and analyze the role of the Latin American context in the development of responsible leaders, which may help understand the boundary conditions for RL in particular contexts; and (3) to provide future directions for the study of the RL phenomenon in developing economies.

This paper is structured as follows. First, a literature review on RL is presented. Then, the method used to find and select the works on RL in the Latin American context is described. Next, the role of context in the RL development in Latin America is reviewed and dis-cussed. Later, the contextual differences between RL in Latin America and the developed countries are examined. Finally, conclusions, limitations, and possible future research scopes are presented.

2. What is responsible leadership?

RL is a developing research area that differs from other traditional leadership theories such as Ethical Leadership (Treviño & Brown, 2005), Servant Leadership (Greenleaf, 2002), Authentic Leadership (Gardner et al., 2011), and Transformational Leadership (Avolio et al., 1999). The main difference from other styles is that RL includes the leader’s concern and involvement in value creation, social and environmental issues, sustainability, and positive changes regarding the stakeholders inside and outside the organization (Pless et al., 2021). This leader-stakeholder relationship implies specific moral and ethical values, new challenges, relationships, motivations, and intentions about society and the environment inside and outside the organization (Pless & Maak, 2022).

Since the responsibility concept may vary between people, cultures, or regions, RL has no unique definition (Waldman et al., 2020). Such complexity reveals the divergence in theories and current approaches to the phenomenon (See Table 1).

Table 1 Responsible Leadership General Theoretical Perspectives.

| Perspective | Responsible Leadership Definition | Main Focus | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relational Perspective | "relational and ethical phenomenon, which occurs in social processes of interaction with those who affect or are affected by leadership and have a stake in the purpose and vision of the leadership relationship" (Maak & Pless, 2006, p. 103). | Values and motivations of the responsible leader towards the stakeholders | •

|

| Kantian Perspective | "intentional actions were taken by leaders to benefit the stakeholders of the company and actions taken to avoid harmful consequences for stakeholders and the larger society." (Stahl & Sully de Luque, 2014, p. 238). | The distinction between actions "to do good" and "avoid harm" |

|

| Global Perspective | "leading responsibly in a global environment means, for instance, ensuring principle-driven and ethically sound behavior both at home and abroad; taking a stance on human rights issues; contributing inactive ways to solving the global environmental crisis; and being responsive to the legitimate expectations of a diverse group of stakeholders" (Pless et al., 2011, p. 240). | Responsibility and obligations of the leader in a global environment |

|

Source: own elaboration.

Regardless of the perspective, RL literature covers theoretical proposals and empirical analysis focusing on antecedents and outcomes over the micro, meso, and macro levels (Miska & Mendenhall, 2018). A more detailed review of these two research paths is presented in the following sections.

2.1 What does the literature on responsible leadership antecedents suggest?

Research on RL antecedents encompasses the responsible leader’s foundations, motivations, values, virtues, and ethical principles to create and develop sustainable relationships and generate value inside and outside the organization (Pless, 2007; Stahl & Sully de Luque, 2014).

Pless’ (2007) influential empirical work sparked renewed interest in the RL antecedents. In her bio-graphical analysis of Anita Roddick’s life (The Body Shop’s founder and leader), she explored the relationship between Roddick’s actions as a responsible leader and her motivational drivers. Pless (2007) defined three intrapsychic drivers focused on the leader as an individual (the need for exploration and assertion, the need for attachment and affiliation, and the sense of enjoyment), and three normative motivational drivers focused on the leader’s relationship with others (the need for justice, the need for recognition, and the sense of care).

According to Pless (2007), Roddick’s identity consists of: “(1) wholeness of values and virtues; (2) wholeness in the sense of being part of something larger than the person […]; and (3) wholeness as a person in the sense of aligning thinking, feeling and acting.” (p. 451). As Pless (2007) stated, RL is intrinsically related to a long-term vision based on values and virtues. This vision goes far beyond the organization and encompasses economic, social, human, and environmental aspects. Also, RL manifests itself in decisive moments that reveal the leader’s character, integrity, ethics, and interest in serving others. Pless (2007) argues that RL leaders develop their characteristics during a lifetime. Also, she concludes that the RL is based on solid values obtained from life experience, influenced by personal relationships and interactions with others, and combined with individual virtues such as passion, love, a sense of caring for others, social values, and purpose (Miska & Mendenhall, 2018; Pless, 2007).

Stahl and Sully de Luque (2014) also theorized the RL antecedents. These authors propose an RL theoretical model with a mixture of certain individual characteristics and specific context factors. This model includes the personal attributes influenced by the proximal and distal contexts (e.g., individual influences, situational, organizational, institutional, and supranational contexts on responsible leader behavior). According to Stahl and Sully de Luque (2014), “the basic premise of the model is that responsible leader behavior is a function of both the person and the environment in which that behavior takes place.” (p. 239)

In their model, Stahl and Sully de Luque (2014) identified individual leader characteristics (micro-level) (e.g., personality traits, cognition and reasoning, value and moral philosophy, affective states, and demographics). Then, in the proximal context (meso level), they recognized the influence of the situational context (e.g., the proximity and distance, the social consensus, the probability of effect, and the benefits to the actor) and the organizational context (e.g., the CSR approach, the code of conduct, the rewards and sanctions, and the ethical climate). Finally, in the distal context, the authors identified the influence of the institutional context (e.g., the national culture, the legal system, the role of stakeholders, and industry competition) and the supranational context (e.g., NGO activism, the role of media, the global governance, and the UN Global Compact). Based on that, the authors proposed that RL is based on a mixture of variables that allows the leader to define their responsibilities and decisions to “do good” or to “avoid harm.”

In general, the literature on RL antecedents started from a more individual level (a micro perspective), considering the relational and motivational interests of the leader (Pless, 2007). Then, it evolved towards an analysis at all levels (micro, meso, and macro), considering the effects of the organizational environment and the cultural, social, political, and economic context on the leader (Stahl & Sully de Luque, 2014). Also, the literature analyzed the development of RL competencies through learning programs within organizations (e.g., Pless et al., 2011; Stahl et al., 2016). In conclusion, the analysis of antecedents seeks to understand the characteristics that precede the RL phenomenon, to identify the leader’s competencies, to understand their development, and to be able to develop responsible leaders.

2.2 What does the literature on responsible leadership consequences suggest?

Regarding the outcomes, RL literature covers the actions and results of the responsible leader to create sustainable value for all the stakeholders. These outcomes include actions related to leadership effectiveness, employees’ attitudes and performance, social change, organization triple-bottom-line (TBL) performance, and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) (Doh & Quigley, 2014; Javed et al., 2020; Maak et al., 2016; Voegtlin et al., 2012; Voegtlin et al., 2020). Voegtlin et al. (2012) proposed a model to analyze RL outcomes across multi-level organizational outcomes (e.g., micro, meso, and macro) and focus on the current global challenges. They defined macro-level RL outcomes as those emerging from interactions bet-ween organizations and society (e.g., legitimacy, trustful stakeholder relationships, and social capital); the meso-level as those emerging from interactions within the organization (e.g., ethical culture, CSR character, social entrepreneurship, and performance); and the micro-level as those attitudes and behaviors resulting from personal interaction with different agents (e.g., OCB, motivation, job satisfaction). The authors concluded that the actions of RL at all levels are essential to face the current challenges of globalization. Likewise, they tested a model involving three leadership roles. They found that RL positively affects outcomes such as favorable stake-holder evaluations, leaders’ perceived effectiveness, and employee engagement with the organization and society.

Doh and Quigley (2014) also conducted research focused on RL outcomes. They proposed two possible ways for a responsible leader to be influential and generate actions and positive effects. The first is a psychological pathway based on psychology that includes, for instance, trust building, ownership, and commitment; second, a knowledge-based pathway rooted on information and knowledge that includes creativity and expertise sharing, among others. The authors indicated that, through these two pathways, the responsible leader promotes specific results at the individual, group, organizational, and social levels that reflect on their CSR actions at a global level.

More recently, Javed et al. (2020) and Mantikei et al. (2020) empirically analyzed the relationship between RL and each dimension of TBL performance considering the mediating role of corporate reputation and innovation. Both studies found that RL has a positive relationship with the social, environmental, and financial dimensions of TBL performance, but they are mediated by innovation. However, Javed et al. (2020) found that corporate reputation only mediated the relationship between RL and environmental performance. Thus, recent studies have demonstrated RL's critical effect on the meso level given that this kind of leadership makes multi-dimensional benefits available to the organization.

The literature on RL outcomes generally encompass-es the micro, meso, and macro levels. It analyzes the influence of the leader’s actions on the results and the CSR and policies in the world. It emphasizes the importance of these actions to create value and gene-rate sustainability inside and outside the organization with social, environmental, economic, and political implications. The research on RL outcomes tends to be oriented to the CSR actions of the organizations in a globalized world.

3. Method

A broad search of peer-reviewed publications was made in the four EBSCOhost (Business Source Ultimate, Academic Search Complete, PsycARTICLES, and PsycINFO) and Scopus databases. These included publications in English, Spanish, or Portuguese from January 1990 to July 2022. EBSCOhost databases were used because they allow for a full-text search. While searching, not all articles focused on Latin America or Latin American countries included this scope in their title or abstract (Waldman et al., 2006). This search combined the keywords “responsible leadership” or “leader-ship” with “corporate social responsibility,” “CSR,” or “stakeholder management” in the title or abstract with words relating to the Latin American region in the full text (i.e., emerging markets, emerging countries, emerging country, Latin America, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic (or República Dominicana), Uruguay, or Venezuela). This search was complemented by a search in the Scopus database using the same keywords in the abstract as in the EBSCOhost search.

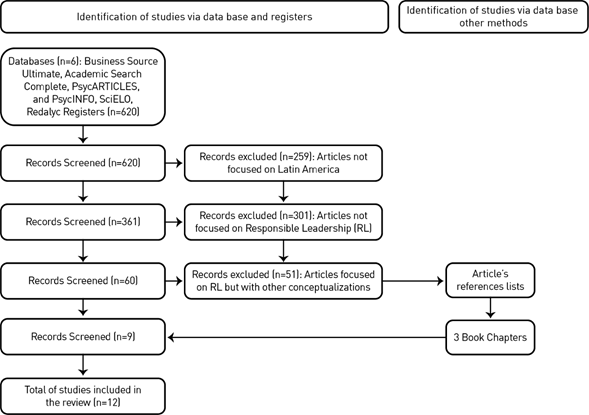

This search yielded 620 theoretical and empirical publications. After eliminating the publications that did not focus on the Latin American context (n = 259), there were 361 publications left. Finally, only publications focusing on RL “as the art of building and sustaining good relationships with all relevant stakeholders” (Maak and Pless, 2006, p.104) and on the Latin American context were retained. Therefore, 59 publications were excluded, leaving nine publications in the sample. Three book chapters discovered in the reference sections of these articles and whose focus matched the inclusion criteria were added to this.

Given that the focus of the analysis was the Latin American context, an additional search was conducted with the terms “líder*” or “leader” and “responsa*” on the SciELO and Redalyc databases, which focus on La-tin American articles. The SciELO database yielded seven publications and Redalyc yielded seventeen, one of which was already included in the original sample. After reviewing all the abstracts, none were related to this article’s conceptualization of RL (e.g., articles focused on CSR outcomes rather than a focus on leadership), and they were not included in the sample. Thus, the total sample resulted in the 12 articles shown in Figure 1. See Appendix 1 for details.

Source: own elaboration.

Figure 1 Responsible leadership in Latin America - Flo diagram of the review.

Examples of the publications that were not retained were those (1) focusing on topics regarding corporate social responsibility or stakeholder management but not on leadership phenomena at the individual level (i.e., Selmier et al., 2015); (2) focusing on topics regarding global leadership but not on stakeholder or corporate social responsibility (i.e., Reiche et al., 2017); and (3) focusing on RL but not on Latin American countries (e.g., Marques et al., 2018) or with a focus in other emerging countries such as Asian or African countries (i.e., Cheng et al., 2019; Witt & Stahl, 2016). Given the limited number of leadership studies in the Latin American region published in management journals (Castaño et al., 2015; Nicholls-Nixon et al., 2011), the small number of publications is no surprise. However, this sample also allowed us to conduct an in-depth analysis of the articles.

4. The role of the Latin American context in responsible leadership development

Studies targeting RL in Latin America suggest that the context may play two different but essential roles. In some cases, the Latin American context appears to enable a proactive RL. In these cases, the context acts as a pushing (driving) force and promotes the development of responsible leaders. In other cases, the Latin American context enables a reactive (rather than proactive) RL. Here, the context acts as a pulling force where a scenario requires or needs help. Organizational leaders are call-ed to contribute to social, economic, and environmental development. Table 2 shows the research done on the context both as a pushing and a pulling force, as well as their main characteristics.

Table 2 The Roles of the Context in the Responsible Leadership Development in Latin America.

Source: own elaboration.

4.1 The context as a pushing force in responsible leadership development

The research on Latin America suggests that the context likely pushes the responsible leader’s development. In these cases, the RL emerges because the personal experiences (in the context) contribute to their moral character and build their sense of responsibility towards society. In this perspective, the context seems to help the leaders develop their ability to make decisions and build sustainable, responsible relationships with their stakeholders. Five studies support this idea and are characterized by privileging the micro-level of analysis: three of them focused on analyzing the development of particular individuals as responsible leaders; the other two studies, in turn, focused on individuals’ educational/training process (future leaders) located in Latin America versus those in developed countries.

Therefore, reviewing and analyzing the context as a pushing (driving) force will follow this logic: First, the three studies focusing on developing a responsible leader will be investigated; then, the two studies examining the educational process of future leaders in the Latin American context are presented. These studies explore the antecedents of RL. Table 3 summarizes the studies pertaining to the context as a pushing force.

Table 3 The context as a pushing factor: Examples, studies, and characteristics.

| Research | Focus | Level | Context Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

• RL’s moral development | • Micro (intrinsic) level: Personal characteristics of the leaders and their development. | • The context contributes to the development of the moral character of the RL |

|

|

• RL’s individual growth via education | • Micro (extrinsic) level: Characteristics and abilities of management students as responsible leaders. | • The context motivates Latin American leaders to engage in RL |

Source: own elaboration.

The first is Maak and Steotter’s (2012) analysis of Martin Burt in Paraguay. Drawing upon the RL model of Maak and Pless (2006), Maak and Steotter (2012) identified five RL relational roles that Martin Burt developed throughout his life. The leader as a steward, servant, change agent, citizen, and visionary (Maak & Pless, 2006). According to Maak and Steotter (2012), from an early age, the responsible leader (Martin Burt) develops an understanding and sensitivity to the social problems in Paraguay. This sensitivity is somehow inherited and strengthened by the influence of close role models in his life, such as his grandmother. Burt grew up in an economically favored family from Paraguay, which allowed him to access a top-quality international education. This gave him a critical view of the world’s socio-economic environment and social issues inside and outside his home country. It could be assumed that his education provided him with tools and allowed him to develop specific characteristics to generate value and social impact and address social problems (e.g., poverty and lack of education) from his organization.

“While his family background helps to explain his motivation to fight poverty,” Maak and Steotter (2012, p. 414) explain, “it is still surprising to see that Martin decided at the age of 15 to dedicate his professional life to the enhancement of civil society.” In other words, a combination of frustration with oppression and a pro-found interest in promoting quality and liberty led to the decision, indicating the relationship between the political context and Martin Burt’s personal history. Based on their research, it could be suggested that Burt’s context somehow explains his motivation to help and avoid poverty in his country and address the social needs of the most vulnerable community from an early age.

In another case study, Van de Loo (2006) analyzed the RL of Fabio Barbosa, CEO of the Brazilian subsidiary of ABN AMRO Bank. Specifically, the author examines the life experiences of Barbosa, the origins of his vision, and how he developed himself as a responsible leader. According to Van de Loo (2006, p. 173): “For Fabio Barbosa, social responsibility is a stance that is part of everything you do. It impacts the relationships with all stakeholders involved, such as shareholders, clients, employees, and suppliers, as well as the society at large”.

Van de Loo (2006) identified critical elements that developed Barbosa’s leadership from an early age. The context in which Barbosa grew up seems to promote his further leadership style and responsibility. Barbosa grew up in an upper-middle-class Brazilian family and had access to top-quality international education. This international exposure appears to have developed his awareness of his country’s social-economic problems, which has become essential for his vision and mission as a leader at ABN AMRO Bank. The author highlighted that Barbosa “felt that with his education and experience, he wanted to use it to make a contribution to his home country” (2006, p.178). Thus, he argues that Barbosas’ RL results from a combination of values, competencies, and skills developed through social education and learning from role models over a lifetime and career. In this line, Van de Loo (2006) paid specific attention to Barbosa’s family role models (father and grandfather) and organizational role models in his development as a responsible leader. In his case, the fundamental values driving Barbosa’s leadership are deeply rooted in his personality. These values were planted in him during his childhood like seeds, thus allowing him to use and live them later in the work environment.

Furthermore, Castillo, Sánchez, and Dueñas-Ocampo (2020, 2022) examined the case of Carlos Cavelier, the owner and “Dream Coordinator” of Alquería S.A., Colombia’s third-largest dairy company. Cavelier is interested in contributing to the development of the most forgotten stakeholders in his organization: the peas-ants, the shopkeepers, and the Colombian children. The authors combine the ideas about RL (Maak & Pless, 2006; Pless, 2007), psychological development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; Magnusson & Stattin, 2006), and moral development (Kohlberg, 1981) to analyze the development of the motivational drivers of Cavelier as a responsible leader throughout his life. Castillo et al. (2020, 2022) found in Cavelier motivational drivers such as the need for exploration and affirmation, the need for attachment and affiliation, the need for justice, the need for recognition, and the sense of care, which seem to explain his RL roles as steward, citizen, servant, visionary, coach, architect, storyteller, and change agent.

In their study, Castillo et al. (2020, 2022) highlighted that the Colombian (Latin American) socio-economical context is an environment in which responsible leaders’ development would not seem easy due to formal and informal institutional weaknesses that promote irresponsible behaviors. Castillo et al. (2020, 2022) argued that the social context in which Cavalier grew up seems to have contributed to his RL behavior. According to them, the proximal environment or microsystem (family and school), and the coherence between the values promoted by his family and those promoted by his school (mesosystems), represented an optimal environment. It was crucial in the development of the RL drivers in Cavelier. Besides that, the authors emphasized that the Colombian rural context (distal environment) in which Cavalier grew up, surrounded by peasant families (who did not enjoy their privileges), was also essential in his development of values such as respect, solidarity, equality, freedom, justice, and service.

Thus, Castillo et al. (2020, 2022) sustain that the context or parenting environment seems to matter in the development of responsible leaders. In this case, the proximal environment (represented by Cavelier’s micro and mesosystem) characterized by the coherence and consistency in developing values and role models contributed to Cavelier’s moral development. Likewise, the distal context (represented by his exo- and macro-systems) characterized by the existence of social and economic needs “tested” (in a real way) Cavelier’s values and moral development.

Based on the findings of Maak and Stoetter (2012), Van de Loo (2006), and Castillo et al. (2020, 2022), three contextual similarities in the development of responsible leaders in Latin America were found. First, all the studied responsible leaders had role models who influenced their ethical and moral character from an early life stage. These role models seem concerned about Latin America’s contextual problems (e.g., poverty, education, and healthcare) and sensitive to the difficulties in their countries and communities, making them also former humanistic and responsible leaders. In the case of Martin Burt (Maak & Stoetter, 2012), for example, he develops an understanding and sensitivity to the social problems of his country from an early age that is somehow inherited and strengthened by the influence of his grandmother (an activist for women’s rights in the United Nations). In the case of Mario Barbosa (Van de Loo, 2006), his family role models (father and grandfather) also seem to provide him with fundamental values for developing his leadership style. Finally, in the case of Carlos Cavalier (Castillo et al., 2020, 2022), his family influenced the development of values such as respect, solidarity, equality, freedom, justice, and service. These studies demonstrate the significance of the proximal context in developing leaders’ moral, ethical, and relational character in awakening leaders’ responsibility toward society and the context in which their organizations operate.

Second, the leaders were raised in a more eco-nomically advantageous context in the three cases. This environment enables them to receive a high-quality education and international training (e.g., Martin holds a master’s degree in public policy, Carlos a master’s degree in public administration, and Fabio a master’s degree in business administration). This top-quality international education seems to have granted them a critical look at the world’s socio-economic environment and social problems, inside and outside their home countries. This education seems to have provided them with the tools to develop specific characteristics to generate value and social impact and address social problems such as poverty and lack of education through their organization. This international exposure seems to have developed their awareness of their country’s social-economic issues that turn out to be essential for their vision and mission as RL in their countries.

Third, in all three cases, the leaders entered national politics. For example, Martin was a minister and mayor, and Carlos was a congressman. However, they dis-covered they could contribute more to society through their respective organizations at some point. The three of them developed strong moral character and a sense of service. They carried out projects with common sense to help the community in their countries, a type of stakeholder often forgotten by the business sector. This political exposure gave them the skills to negotiate and build relationships with different stakeholders. Despite the cultural differences between the three countries, it is clear that the Latin American context was critical in their understanding of societal problems and development as responsible leaders.

Furthermore, the studies of Sánchez et al. (2020) and Dugan et al. (2011) provide evidence that the context can push Latin American leaders to engage in RL from an early age. In their study, the authors investigated the relationship between RL styles and ratings regarding corporate social responsibilities in 1,833 business management students (mean age of 22) from six Ibero-American universities. They concluded that, in Latin American countries, business students with a relational RL style also have an interest in diverse stakeholders. Students with a relational leadership style are those interested in helping and supporting colleagues, subordinates, and teams, working with socially disadvantaged people, and being helpful to their communities. Likewise, such students have a complementary view of the importance of CSR initiatives.

On the other hand, in a study comparing college students from Mexico and the US, Dugan et al. (2011) found that they may differ in their capacities for socially RL and that the Mexican context contributes more to developing these responsibilities than the American context. According to them, undergraduate courses in the US culture are more likely to emphasize “productivity, outcome achievement, rationality, and reliance on data and measurement.” (p. 466). Mexican courses, on the contrary, are more likely to emphasize “reflection, process orientations, and learning through intuition and observation” (p. 466).

Thus, when examining the possible effects that the educational context can have on the style that future leaders adopt, the works by Sánchez et al. (2020) and Dugan et al. (2011) highlight that the idiosyncrasies of Latin American countries seem to awaken in future leaders an orientation towards the inherent social and economic needs and shortcomings of such contexts. Therefore, future leaders educated in these contexts often show an orientation towards a leadership style that considers the needs of their organization and stakeholders: a leadership style characterized by responsibility.

In general, contrary to the popular notion that adverse conditions will develop irresponsible leaders, in the five cases in which context seems to work as a pushing force, such social, economic, and political conditions promote the leader’s sensitivity to the needs of others and moral virtues, and their responsibility toward society.

4.2 The Context as a Pulling Force in Responsible Leadership Development

Research on Latin America suggests that the context is likely to act as a pulling force in the RL’s development. As such, the context seems to demand responsible leaders’ attention, acting as an enabler of a reactive (rather than a facilitator of a proactive) RL. Therefore, the phenomenon of RL emerges because the leader assumes the responsibility to contribute to a society that demands development. Six studies support this view and are characterized by prioritizing the meso and the macro level of analysis.

Such studies show how the context can be the recipient of RL initiatives to address socio-economical voids characteristic of developing economies. Thus, organizations contribute to these contexts through RL and seek to overcome some of the complex social, economic, and environmental conditions. The studies are divided into two parts: five studies analyze the CSR actions of RL in Latin America and the consequences for their organizations, and one study analyzes the CSR actions undertaken by multinational organizations in their Latin American subsidiaries. Thus, they examine the consequences of RL. Table 4 summarizes the studies pertaining to the context as a pulling force.

Table 4 The context as a pulling factor: Examples studies and characteristics.

| Research | Focus | Level | Context Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

• CSR actions of RL in Latin America and the consequences for their organizations | • Organizational (meso) level |

|

|

|

• CSR actions undertaken by multinational organizations in their Latin American subsidiaries | • Organizational (meso), societal, and/or institutional (macro) level |

|

Source: own elaboration.

Waldman et al. (2006) developed theoretical and empirical associations between CSR decision-making and three cultural dimensions of the GLOBE project: institutional collectivism, in-group collectivism, and power distance. Using data from GLOBE (House et al., 2004), the authors analyzed the cultural and leadership predictors of top management CSR values. In this study, the authors found evidence to suggest that demographic, economic, and cultural factors (e.g., power distance) predict the development of CSR leadership, whose actions are based on relationships with internal and external organizational stakeholders.

Waldman et al. (2006) suggested that leaders perceive government agencies as less efficient in dealing with social problems in developing countries. Thus, leaders might feel more responsible for the community and more motivated to generate social change. These findings align with studies using the GLOBE project regarding RL in other countries (e.g., Asian countries). As Witt and Stahl (2016) argue, “executives in different societies hold fundamentally different beliefs about their responsibilities toward different stakeholders, with concomitant implications for their understanding and enactment of responsible leadership” (p. 624). The authors suggest that each culture’s human approach (hu-mane orientation) can explain or influence the leader’s predisposition towards responsible behavior. They refer to the human approach as how society promotes and encourages individuals to be fair, selfless, generous, and committed to others.

Based on Maak and Pless’ theoretical framework (2006), Mària and Lozano (2010) examined the roles and virtues of Sinforiano Cáceres in Nicaragua focusing on his role as a builder of ethical and sustainable relationships with the different stakeholders. It is important to note that the emphasis of this research differs from the literature that shows the context as an enabler of a proactive RL. In this case, the authors did not analyze whether the problematic conditions (social, economic, and political) contributed to Caceres’ leadership development or the specific characteristics of the leader’s upbringing context. Instead, the study focuses on the valuable work that a leader likely does in a context that needs it. The authors identified five different essential RL skills to address social inclusion problems: i) The ability to direct his attention to his organization and society; ii) the ability to articulate the interests of external and internal stakeholders; iii) proactive work to promote social inclusion and prevent the marginalization of certain groups; iv) creativity to generate new forms of work, and self-confidence to develop and strengthen dialogue and trust between stakeholders; v) active work to promote spaces of interaction and trust between different groups.

Furthermore, Jaén et al. (2021) studied the roles of three responsible leaders in building inclusive ventures at the Base-of-the-Pyramid: Benjamin Villegas (Colombia), Alex Pryor (Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina), and Tyler Gage (Ecuador). According to Jaén et al. (2021), the Latin American context is critical in shaping these responsible leaders. Most importantly, they argued that “context matters, influencing how RL is operationalized and de-fined” (p. 467). This paper is comparable to Mària and Lozano’s study (2010) of the roles and virtues of Sinforiano Cáceres in Nicaragua. It focuses on the work that leaders may undertake in circumstances that require this type of leadership.

Jaén et al. (2021) emphasized that contexts characterized by institutional voids promote RL with a solid ethical basis that understands the context’s needs: “The physical and institutional infrastructure that is usually taken for granted in other settings is simply not there, which imposes the need to find viable second-best alternatives on the part of the entrepreneur. This entails two tasks: imagining what is possible and turning that vision into reality” (p. 1). These RL are thus critical in invite multiple stakeholders to participate in successful supply chains. Additionally, the authors identified two new roles that RL adopts in these contexts: the role of a catalyst, which brings together “various pieces of the puzzle and enables action.” (p.10); and the role of a social innovator, which is grounded in these contexts and reveals the need of innovation to provide novel solutions for in-need contexts.

Davila et al. (2013) analyzed the work of global leaders from the stakeholders’ perspectives in another study. To illustrate the type of humanist leadership in Latin America, the authors cited several illustrative cases such as Ternium, a leading steel company in Latin America, which is actively committed to develop its employees and local communities through health, education, art, culture, the environment, sports, and social integration initiatives. They also explore examples of some multinationals (e.g., Santander, Telefonica, Nestlé, or FEMSA) that have decentralized their NGOs to operate according to local needs. This decision has allowed foundations to achieve goals beyond their business and implement broader CSR practices in Latin American countries. Thus, according to Davila et al. (2013), global leadership requires identifying stakeholders and managing relationships with them horizontally-as equals-to generate trust and legitimacy and thus understand their needs.

For Davila et al. (2013), “the stakeholder perspective has specifically helped us identify key contextual elements in the Latin American region, including the role of the enterprise as a social institution that contributes to human and social development, the value granted to the person within collectivistic societies, and the pragmatic character of governmental public policies related to employee management” (p. 186). In this study, the authors developed ideas similar to those of Maak and Pless (2006) and applied them to the Latin American context. The authors highlighted that responsible leaders of global organizations must behave as citizens of the world and positively use their power and privileges to help society. Hence the role of context as a pulling force.

Davila and Elvira (2012) analyzed the psychological, sociological, and historical perspectives that characterize Latin America’s leadership styles. According to the authors, leadership in Latin America is deep-rooted in a paternalistic leadership style “based on social bonds via the relationship of reciprocity.” (p. 550). This style shapes how leaders create relationships and behave with their employees and stakeholders. Therefore, combining it with the Latin American institutional weaknesses and governments that continuously struggle to address socio-economical concerns, might explain why and how some leaders in the region are motivated to compensate their employees and stakeholders, and behave as RL.

The authors labeled the leadership style focused on stakeholders in Latin America as “humanistic leadership.” According to them, it is associated with transformational leadership as it considers the stakeholder not a resource of the organization but rather another human being. They emphasized that leadership in the region is based on the social relationships with diverse organizational stakeholders that characterize responsible leaders. Besides that, the authors acknowledged a disposition towards the community based on trust, respect, and reciprocity in Latin America. For example, if organizations receive resources from the community, then the community should receive reciprocal resources from the organizations. That exchange requires organizations and leaders to be responsible and develop more CSR programs and policies.

Stahl et al. (2016) discussed Western organizations’ Global Responsible Leadership (GRL) challenges and their CSR policies in developing countries such as Latin America. The authors state that the GRL responds to the global economic crisis and is also the result of pressures from NGOs, communities, and other external actors on corporations to self-regulate and play an active role as global citizens. According to the authors, Western multinationals’ global leaders are generally familiar with strong judicial institutions and systems rather than weak institutional contexts in developing economies. Therefore, working in developing regions takes responsible global leaders out of their comfort zone and make complex decisions.

Stahl et al. (2016) identified three approaches of responsible global leaders in Western multinational enterprises (MNEs) when doing business in developing economies. First, the global approach, where leaders focus on universal guidelines such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals and apply them to each cultural context. Second, the transnational approach, where leaders simultaneously focus on global issues and local concerns. And finally, the local approach, where leaders focus on local interests and concerns. The transnational and local approach emphasize the critical role of global leaders in understanding local realities (pulling) and acting as responsible leaders. Additionally, while pursuing a global strategy that promotes universal principles, leaders must consider contextual particularities to accomplish their goals.

For example, the authors described how the Newmont Mining Corporation had to rebuild its relationship with local communities in Peru due to a mercury spillover that generated health problems in the area. This example illustrates how global leaders follow universal guidelines without focusing on specific context-dependent demands and needs. In this example, the context pulled the leaders to care about the community and act as RL. For Stahl et al. (2016), responsible leaders

“must exhibit an appreciation for the differences in CSR and ethics found in these environments as opposed to their experience in more stable and predictable conditions in Western countries […] and must recognize that differences exist among emerging economies due to regional heterogeneity, different political systems, their speed of economic development, and the enactment of institutional reforms.” (p. 100-101)

Finally, the authors conclude that MNEs should develop RL with the skills to lead responsibly in challenging contexts, such as developing economies. Focusing on social entrepreneurs in Latin America and using the theoretical framework of Maak and Pless (2006), Table 4 summarizes the context’s roles in developing RL in Latin America.

4.3 Differences in responsible leadership development in developing and developed economies

Let us turn to an important question: Do the contexts in developing economies influence the emergence of RL in a different way that developed economies? The analysis suggests that RL development varies in several forms. This does not mean that the developed countries’ leaders cannot access or experience developing economies that promote their moral and relational character and cultivate their RL and does not suggest other ways leaders in developed economies can build their RL at an early or later stage in life. However, this indicates that the contextual conditions in developing countries such as Latin America are different; therefore, the leaders firsthand experience in developing countries and their proximal environment forges their moral character differently.

These results align with research on developing globally responsible leaders through service-learning programs (Pless et al., 2011). In their study, the authors analyzed a leadership development program for MNEs. They sent some leaders to developing economies to work in cross-sector partnerships with NGOs, social entrepreneurs, or international organizations and found that leaders who participated in the program developed a “responsible mindset, ethical literacy, cultural intelligence, global mindset, self-development, and community building” (p. 237). This study suggests the importance of firsthand experiences in the leader’s understanding of societal challenges and organizational responsibilities. Likewise, the research by Muff et al. (2022) showed that participants in RL training programs in less developed regions (such as Africa) outperform participants in other regions, such as North America and Europe, since self-awareness emerged in those participants as a critical factor for RL. In this line, business education research has suggested the importance of service-learning programs for students. They travel to developing economies to offer their work and, in return for their international experience, they develop their moral, ethical, and leadership character (Godfrey et al., 2005).

5. Limitations and future research

Like any research, the review work is not exempt from limitations. For example, this study was limited to research published in scientific databases and, thus, to top academic journals. Unfortunately, scientific articles on RL in Latin America are relatively scarce compared to literature in the United States, Europe, or other developing regions such as Asia. Although there may be different RL academic articles (e.g., articles published locally in university journals), there is relatively little research on RL in the region. Indeed, the search in two databases focused on the Ibero-American context yielded no new articles to be considered in this review.

This work aims to encourage future research on responsible leaders in Latin America-and in other developing economies-considering not only the micro- (individual) but also the meso- (organizational), and the macro-level (institutional). Understanding how these leaders evolve, how they develop moral character, and what motivates and concerns them could help us better understand and compare the RL phenomenon in the region. A broader sample of responsible leaders’ lives and work in developed and developing countries would enable a comparison among different regions, which may help build a general theoretical model of the RL phenomenon.

Future research may also include an analysis to understand how leaders make sense of or recognize their responsibilities as leaders and what role the culture plays in these understandings. This research could help understand how and when Latin American responsible leaders reach out to stakeholders or if the different stakeholders believe responsible leaders should fill social, economic, and environmental voids.

Further, given that social entrepreneurs are also interested in providing solutions to society, future re-search could bridge the findings on social innovation and social entrepreneurship at the individual level with RL research. Understanding the similarities and differences between responsible leaders and social entrepreneurs could help theorists explain how key actors develop their character, networks, societal concerns, and, most importantly, their roles as responsible leaders. Thus, we encourage future research and literature reviews to look at different approaches and models that could have been used to study characteristics that might be indirectly related to responsible leadership (e.g., socially responsible entrepreneurs).

Finally, most of the empirical studies identified in the literature were qualitative. Future research may develop quantitative studies that enable empirical testing of the extant theoretical models. For example, future research can include empirical studies based on Stahl and Sully de Luque (2014) or a combination of different theoretical models. Likewise, quantitative research could analyze other consequences of the RL. Because the incorporation of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria has become necessary (see the 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer, Bowen, 2022), organizations and their directors seem to require more responsible leadership. As such, an important new path for research is analyzing the relationship between the RL style and the implementation of ESG criteria. The relationship between RL and TBL performance indicators could be studied, for example, by considering the possible mediating effect of the incorporation of ESG criteria as a strategic issue in the organization. This is because, although the relationship between LR and TBL performance has begun to be studied (Javed et al., 2020; Mantikei et al., 2020), there is still a lack of understanding of how this leadership style has repercussions on social, environmental, and financial benefits in organizations.

As stated, some studies have already examined the relationship between LR and TBL. Still, none have questioned whether this relationship may vary depending on whether the organization operates in developed or developing contexts. Due to the pulling effect found in this work, it is conceivable that the direct and mediated relationships appear or become more important in contexts where the demands (or the needs) of the LR are more significant, as is the case in developing economies. Additionally, given the findings of this review, future research could analyze the possible (moderating) role played by the social, environmental, economic, and political context in which the mediated relationship occurs.

6. Conclusions

This paper reviews the extant literature on RL focusing on the Latin American context. The role of the context in the RL’s development was analyzed and we found that it could play two different roles: first, the context can act as a pushing force to play a formative role and promote the leaders’ development, particularly their moral character; furthermore, the context can act as a pulling force where the leader assumes the responsibility to contribute to a society that needs it. Thus, this review suggests that the RL phenomenon is not only nested in the specific context in which it takes place (pulling RL) but also develops and defines the emergence of responsible leaders (pushing RL).